|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Nov 12, 2014 9:57:51 GMT

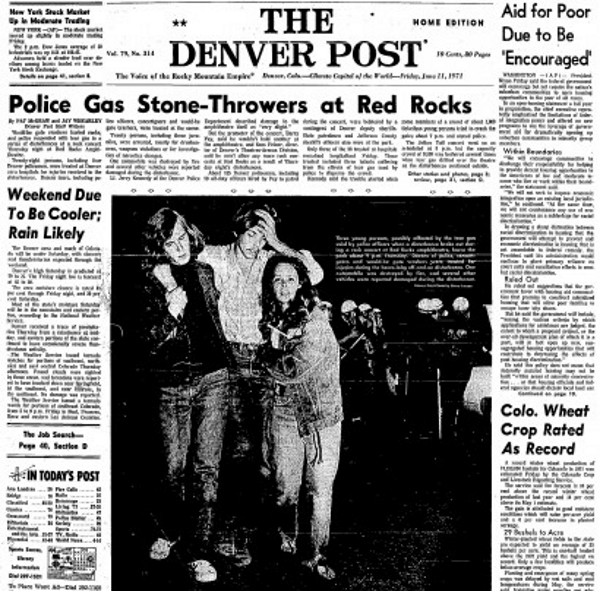

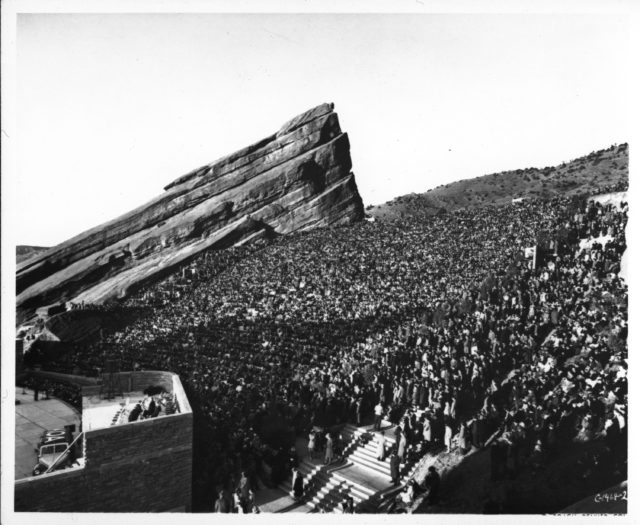

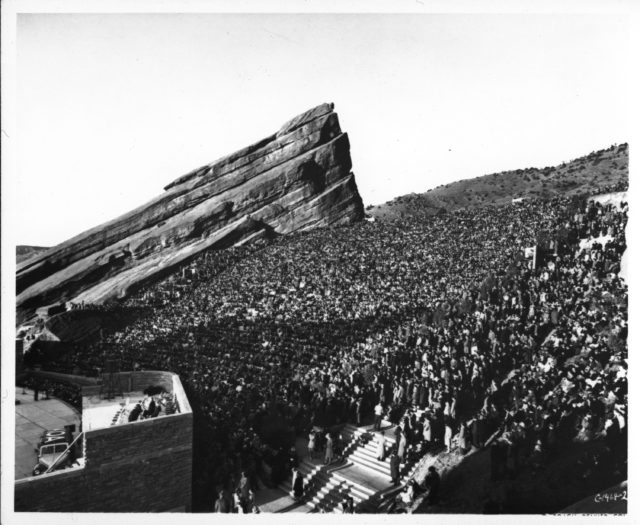

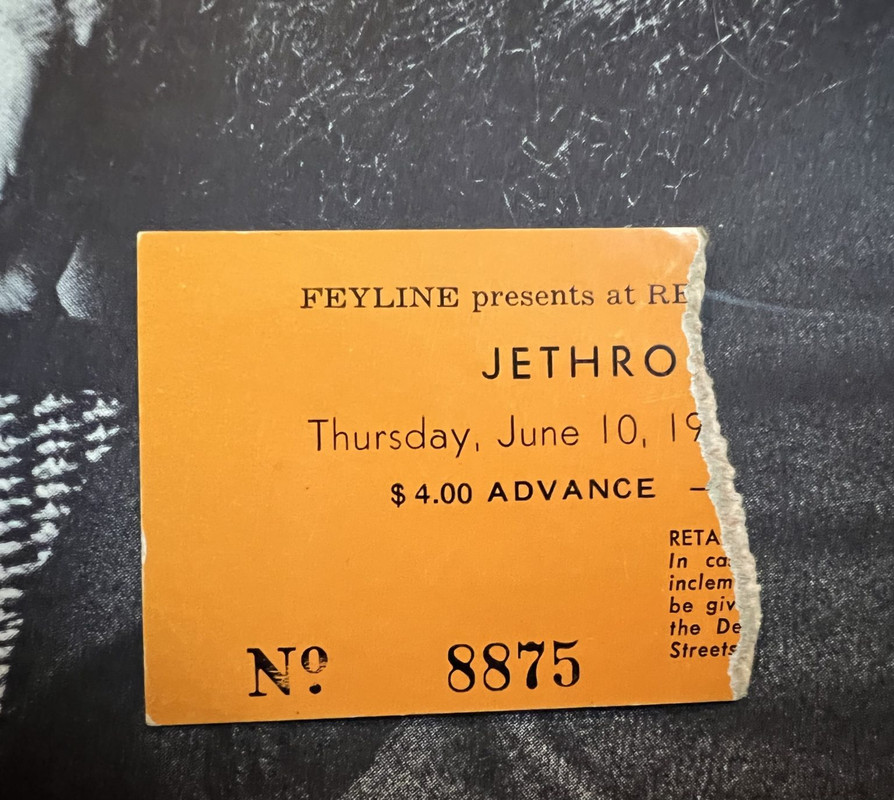

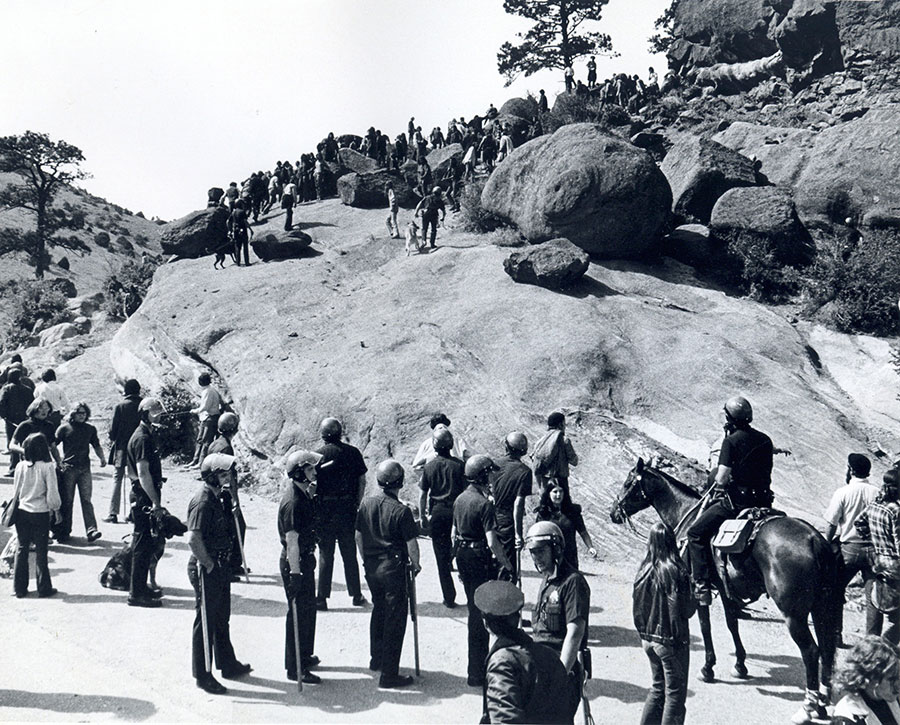

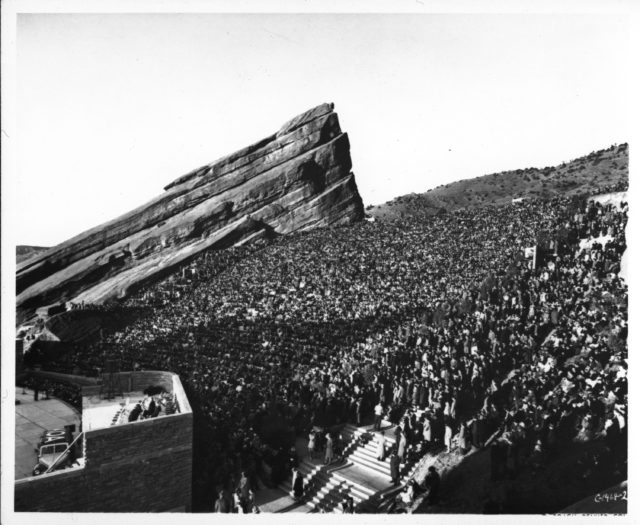

Worth a possible repost to remind ourselves of the mayhem and shenanigans at this concert  Jethro Tull's '71 Red Rocks concert forged a place in rock history Jethro Tull's '71 Red Rocks concert forged a place in rock historyBy Ricardo Baca Denver Post Pop Music Critic POSTED: 06/05/2011 www.denverpost.com/ci_18194571Forty years ago, Jethro Tull played an apocalyptic show at Red Rocks Amphitheatre amid tear gas, unruly crowds, hurled rocks, violent police officers and a swooping police helicopter. It was to be the end of rock 'n' roll at Red Rocks forever. And for the five years after the concert, there was no rock music at the legendary mountain amphitheater. "It was an overreaction by the police at the time, who had helicopters in the air," Tull frontman Ian Anderson said recently from his office in southwest England. "We charged through police roadblocks, and I ran straight onto the stage and talked to the audience. (The police) knew there would be a full-scale riot if they arrested me." Anderson laughs about it now, calling it "a Top 10 strange/weird moment" while discussing his band's Red Rocks date, scheduled for Wednesday, only two days shy of that fateful show's 40th anniversary. It's fitting that Tull is playing Red Rocks on this tour, also the 40th anniversary of the record they were touring then, "Aqualung." So what exactly happened that night in June 1971? From 1,000 to 2,000 fans showed up without tickets to the sold-out concert, and they were directed by Denver police to a side of the mountain where they could watch the show. Some stayed there. Others climbed a wall into the venue. Others charged the gates en masse. Back-up officers were called, and police chief George Seaton came out in the helicopter and dropped tear gas on the unruly masses himself. But the gas spread into the amphitheater, where Livingston Taylor was opening the concert, and suddenly a bad situation got worse. "Backstage looked like an aid station, with doctors and patients sprawled out everywhere," remembered retired promoter Barry Fey. "Boy, did I (mess) up. I didn't realize how big they were. We should have done two shows." It's hard to imagine now, but rock music wasn't always welcome at the Morrison amphitheater. It was already a hard sell in city-owned venues, Red Rocks included, because of a violence at an Iron Butterfly concert at the Auditorium Arena in the late '60s. But Fey had specially petitioned for the Tull concert, and he got it. "Barry learned the hard way that you have to get three or four nights with an artist like that," said Jerry Kennedy, who was a captain with the Denver Police Department in 1971 and later a division chief. "I was running the police up there, and the place was under assault by thousands of people who wanted to get in. They decided they were going to rush the place, and that's what caused the battle. "They were throwing rocks. And I didn't see it, but I heard that some of the officers were throwing rocks back at them. It was the first real incident of that kind that I'd seen." Amid all of this, Tull was devising a way to enter the amphitheater, which had been blockaded by the police. Anderson remembers charging through the police barricade and knowing that he was the only person who could calm the capacity crowd — which was swimming in tear gas at the moment. "(The police) tried to turn us back and say, 'You're not allowed to go up there,' so we just charged the gate," Anderson said. "We jumped out of the cars and ran straight on stage to talk to the audience. "It was like the Russians putting a flag on the ocean bed under the Arctic ice. Once you've done it, staked the claim, it's tough to dislodge you. Once I was on stage in front of a microphone, they cops realized that they had to stand back." Anderson soothed the crowd and told them they were going to get a full set of music. He told them to put clothing over their mouths, and he encouraged parents with babies and small children to come to the apron so they could access the makeshift hospital set up backstage. An iconic moment is forged "People were passing babies down through the audience," Anderson said. It was a mess of an evening. But like Woodstock and Altamont before it, the concert was also a snapshot of America as it formed its relationship with rock 'n' roll. "Back in the early '70s, they didn't know how to cope with rock concerts and rock people," Anderson said. "The big production and how the audience behaved. . . . People now have more understanding, and civil and social savvy. They have an awareness about what it all is." Exiting the amphitheater proved to be as difficult as entering for the band, Anderson remembered. "(The police) tried to get us on the way back down," he said. "They were looking for us, but we were hidden under blankets in the back of a station wagon. They didn't find us, and we got out of town." But the band left a trail of controversy. Police chief Seaton recommended a ban on rock concerts at Red Rocks. Mayor William McNichols said there wouldn't be rock shows there as long as he was mayor. And even Fey agreed, telling The Denver Post at the time that he wouldn't throw any more rock concerts there. Of course, that didn't last long. Fey sued the city in 1975, and a U.S. Circuit Court judge ruled in his favor. As Fey remembers it, the judge put this question to Denver leaders: "Who do you think you are, czars? You're going to tell the people what they should listen to?" Rock returned to the Rocks in '75, and Fey's popular "Summer of Stars" found its start in '76. "We went on to do hundreds of concerts there without a lick of problems because (Barry) got a handle on the problem," retired division chief Kennedy said. "But in terms of problems, I encountered at venues over my career, that ranks in the top two or three." And it would have been worse if Tull had taken advantage of the act-of-God clause in its contract. "The clause says that if anything crazy happens beyond the control of the band, they have the right not to play," Fey said. "But he did play, and he played a full set. "Ian Anderson is still my hero to this day. He went up there and hopped around with his flute and actually played a full set in the middle of the tear gas, in the middle of everything." |

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Nov 12, 2014 17:01:01 GMT

Worth a possible repost to remind ourselves of the mayhem and shenanigans at this concert  Jethro Tull's '71 Red Rocks concert forged a place in rock history Jethro Tull's '71 Red Rocks concert forged a place in rock historyBy Ricardo Baca Denver Post Pop Music Critic POSTED: 06/05/2011 www.denverpost.com/ci_18194571"Back in the early '70s, they didn't know how to cope with rock concerts and rock people," Anderson said. "The big production and how the audience behaved. . . . People now have more understanding, and civil and social savvy. They have an awareness about what it all is."  Video by Greatfulweb 8-|LINK Video by Greatfulweb 8-|LINK  Image by Mike Moran Image by Mike Moran |

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Mar 24, 2018 8:04:59 GMT

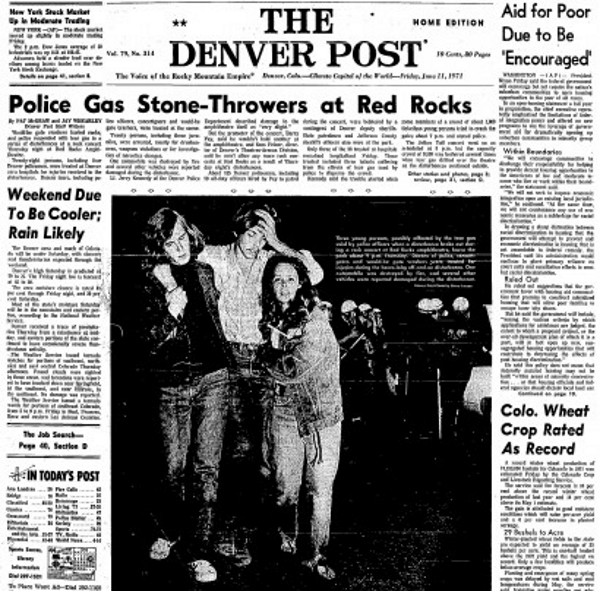

history.denverlibrary.org/news/red-rocks-riots-and-rock-n-roll-birth-summer-stars Gateway Creation Park and Mt. MorrisonRED ROCKS, RIOTS & A ROCK 'N' ROLL REVIVAL: Gateway Creation Park and Mt. MorrisonRED ROCKS, RIOTS & A ROCK 'N' ROLL REVIVAL:

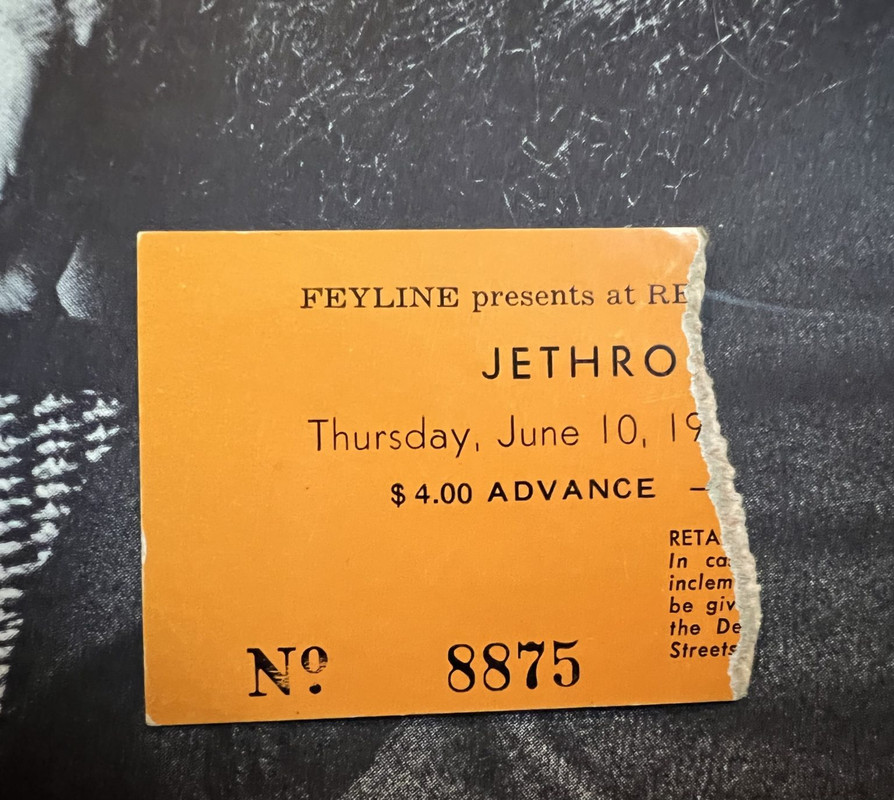

THE BIRTH OF THE SUMMER OF STARSby BRIAN K. TREMBATH on May 1, 2017Denver News Red Rocks ParkBarry FeyColorado On June 10, 1971, a large group of rock fans attempted to bum-rush the gates at Red Rocks Amphitheatre in an effort to see the band Jethro Tull. In the aftermath of that event, the City of Denver imposed a ban on all "rock" shows at the venue, which didn't turn out quite how the City (mainly Mayor Bill McNichols) planned. In fact, the city's rock ban actually wound up spurring on one of the most successful concert series of all time and catapulted Red Rocks into the realm of concert venue legend. They Came from the HillsIf you're having trouble imagining how a Jethro Tull concert could turn into a riot, it might be a case of, "You had to be there to understand." In the late 1960s and early 1970s, plenty of young people felt as though music was an entity that shouldn't be commercialized. They were also not above using the full force of youth to rush into concerts, as was evidenced at the legendary Woodstock Festival. That dynamic was in full effect at Red Rocks that night when thousands of fans who hadn't purchased tickets congregated in the hills surrounding Red Rocks to catch a free listen to the long sold-out show. The trouble began when the "hill people" decided that they should just go ahead and force their way into the amphitheater. This did not go down well with the Denver Police Department, who have long held jurisdiction at Red Rocks on concert days. What happened next was recounted by Chris Van Ness in the June 18, 1971, edition of the Los Angeles Free Press: The police, feeling that it would be impossible to maintain security in any other way due to the rough terrain, began dropping tear gas out of helicopters which were flying a dangerously low watch over the crowds. Rather than acting as a deterrent, the tear gas seemed to spur the now-rioters on to further acts of violence As more tear gas began to fill the amphitheater at an alarming rate, the gate-crashers and audience alike began to pick up bottles and rocks to use as ammunition against the police. One car was overturned and burned, and many people suffered injuries ranging from broken bones to gas inhalation. Not only did the tear gas not quell the riots, it made its way to the stage at the base of the natural amphitheater. The scene could only be described as bedlam, and it had the potential to be a lot worse.  Denver Post, June 11, 1971Welcome to World War 3 Denver Post, June 11, 1971Welcome to World War 3Backstage at Red Rocks, Barry Fey and the members of Jethro Tull were faced with a conundrum. They could cancel the show and send the paid audience straight into a riot, or they could play the show as planned. To their everlasting credit, the members of Jethro Tull decided to go on with the show. Jethro Tull lead singer Ian Anderson took to the stage with guitar in hand and greeted the audience saying, "Welcome to World War Three!" And with a full-scale riot playing out in the hills surrounding them, and clouds of tear gas wafting onto the stage, Jethro Tull proceeded to play their full set. The band's commitment to playing on earned them praise from both the Denver Police Department and Fey, who praised the band in the Los Angeles Free Press saying, "God bless those guys. They're the most professional group I've ever worked with. I don't know anybody else that would have stayed on through all that." Rock 'n' Roll AftermathReaction to the events at Red Rocks that night came swiftly from Denver Mayor Bill McNichols. The very next day, the mayor swiftly imposed a ban on all rock shows at Red Rocks saying: As long as I'm mayor, this city is not going to be turned over to rock-throwing hoodlums. If they think they're going to be allowed to run free, attacking innocent people and police officers, they have another guess coming. McNichols was hardly alone in his view on the future of rock 'n' roll at Red Rocks. Caught up in the moment, a clearly frustrated Fey said that he was done promoting rock shows at Red Rocks. In an interview with the Denver Post on June 11, he said, "If they (the rock artists) want to come into the (Denver) Coliseum (instead of Red Rocks), we'll do it. But most of them know of Red Rocks and wanted to play there." Though Fey would ultimately change his tune regarding Red Rocks, Sam Feiner, the director of the city Theatres-Arenas Division, was firm in his stance that Red Rocks's time as a rock venue had, "definitely ended." To that end, upcoming shows by hard rock heroes Poco, Chicago, and Stephen Stills were canceled. The Blame GameIn the aftermath of the riot, there was plenty of blame to go around. While the Denver Police were accused of overreacting to the situation by dropping tear gas, most of the blame was rightly aimed at the gate-crashing rioters. At the Los Angeles Free Press, Van Ness said, "When it comes to placing blame for the events of last Thursday evening, it must rest with the kids who tried to crash the gate. But the rest of the chemistry is an all-too-familiar formula. The police reacted with fear and stupidity." At the Rocky Mountain News, music critic Thomas MacCluskey pulled no punches in a column titled, "Rock Rowdies Ruin it for Everyone." MacCluskey pointed out that this was hardly the first time that Denver music fans had acted up. He recalled that in August 1968, a riot had broken out at an Aretha Franklin show at Red Rocks after the legendary performer told the crowd that she would not be playing because she hadn't been paid. That resulted in a one-year ban on rock shows. MacCluskey used that as a jumping-off point to school an entire generation for its entitled behavior. "Yes, you 'get-something-for-nothing' generation—in fact, 'get-everything-for-nothing' fools—you caused a one-year ban on rock concerts then...You're just too cute for words." The angry critic went on to predict that there wouldn't be any rock shows at Red Rocks, "...until your little brothers and sisters come along and realize that what you're trying to do is an utter impossibility. There is no 'something-for-nothing' in this universe." MacCluskey was right, for a few years anyway.  Barry Fey tears while on stage at Red Rocks on Tuesday, April 15, 2008 in Morrison, Colo. Going where the public doesn't see at the famous Red Rocks Amphitheater with former promoter Barry Fey. (photo by ©Linda McConnell/Special to the Rocky)Barry Fey vs. The Man Barry Fey tears while on stage at Red Rocks on Tuesday, April 15, 2008 in Morrison, Colo. Going where the public doesn't see at the famous Red Rocks Amphitheater with former promoter Barry Fey. (photo by ©Linda McConnell/Special to the Rocky)Barry Fey vs. The ManMayor McNichols was not kidding when he said that rock shows at Red Rocks were a non-starter, as the 1972 Red Rocks schedule neatly illustrates. That summer's lineup did not rock, even a little bit. Artists on the bill that year included Joan Baez, Pat Boone and the Carpenters. And that's the way it was, right up until Fey took the City to court and won the right to once again book rock acts at Red Rocks. With a dash of typical Fey flair and marketing finesse, the legendary promoter christened the now-familiar, "Summer of Stars" series in 1976. The Bicentennial summer's lineup was considerably more dynamic than it had been in 1971-1975. Acts on the bill included Neil Young, Stephen Stills, David Crosby, Willie Nelson and the Average White Band. (Remember to view these bands through the lens of 1976, when acts like this represented mainstream rock 'n' roll and were considered to be somewhat anti-establishment.) That summer launched Red Rocks into the stratosphere and as the Summer of Stars established itself, Red Rocks became America's premiere outdoor music venue.  Pictures of Red Rocks Amphitheater shot in Morrison, Colo., Friday, Aug. 12, 2005. (MATT NAGER/ROCKY MOUNTAIN NEWS) Pictures of Red Rocks Amphitheater shot in Morrison, Colo., Friday, Aug. 12, 2005. (MATT NAGER/ROCKY MOUNTAIN NEWS) *** Red Rocks ForeverFrom U2's iconic "Under a Blood Red Sky" performance in 1983 to dozens of sold-out nights with the Grateful Dead, and a list of artists that's too long to mention (but is conveniently listed on the Red Rocks' Concert Archive), Red Rocks has offered something for everyone. What's more, an evening at Red Rocks is always tinged with Colorado's natural beauty—the twinkling city lights serving as an almost magical backdrop to the music coming from the stage. Red Rocks is also a favorite spot for artists and plenty of aspiring artists have it on their bucket lists. The memorable amphitheater is so far ahead of the curve that Pollstar Magazine, a trade journal for the concert industry, awarded Red Rocks it's Best Outdoor Venue Award 11 years in a row. To give other outdoor venues a chance, Pollstar went ahead and changed the name of the accolade to the Red Rocks Award in 2001 and took Red Rocks out of the running entirely. Of course, anyone who has ever attended a show (or graduation or church service or film) at Red Rocks knows what a special place it is and how much it means to the people of Denver. And while there have been plenty of rock shows at Red Rocks since the ban was lifted, there hasn't been anything quite like the night Jethro Tull fans almost ruined Red Rocks for everyone.

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Jul 24, 2018 6:21:44 GMT

www.theeagle.com/news/nation/a-rocking-good-time-in-thin-air/article_07b77cad-7e16-5398-b751-2b31f0dd98e0.htmlA rocking good time in thin airBy Christopher Reynolds Los Angeles Times (TNS) 18 hrs ago 0 MORRISON, Colo. — It was a half-cloudy night at Red Rocks Amphitheatre, with boulders looming and distant lightning in the eastern sky. Singer Colin Meloy was on stage with the Decemberists, chatting up the audience. “There are very few places to play in the world that still make me nervous, and this is one of them,” said Meloy, who has been touring for close to 20 years. “It feels like we should be giving a talk on grizzly bear management.” Red Rocks, 16 miles southwest of downtown Denver, is an American outdoor music venue like no other. The stage and audience areas are sheltered between a pair of 300-foot monoliths, Ship Rock and Creation Rock, with another boulder anchored behind the stage, bouncing sound forward. Whether you’re in the audience or on stage, occupying Red Rocks is like being held in the palm of a vast sandstone hand. LINKThe Beatles played in 1964 (leaving about 2,500 tickets unsold at $6.60 each). Jimi Hendrix came in 1968. When Jethro Tull appeared in 1971, legions of ticket-less fans tried to breach a fence, security forces let loose with tear gas, and a five-year rock ‘n’ roll ban began.

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Jul 30, 2018 6:17:06 GMT

www.latimes.com/travel/la-tr-letters-20180729-story.html#Red Rocks? It rocks

Thank you for the excellent article on Red Rocks Amphitheatre [“A Rocking Good Time in Thin Air,” by Christopher Reynolds, July 15]. It brought back fond memories for me.

As a former resident of Denver and Golden, Colo., I attended many shows there, beginning with the Smothers Brothers in the early ’60s and including the infamous Jethro Tull “tear gas” show in June 1971. (As many as 2,000 fans showed up without tickets; some tried to break through the gates, and tear gas was used, spreading over the audience.) The next year, the band entered the stage for its show at the Denver Coliseum wearing gas masks.

Chuck Butto

Ontario

|

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Jun 13, 2019 1:34:17 GMT

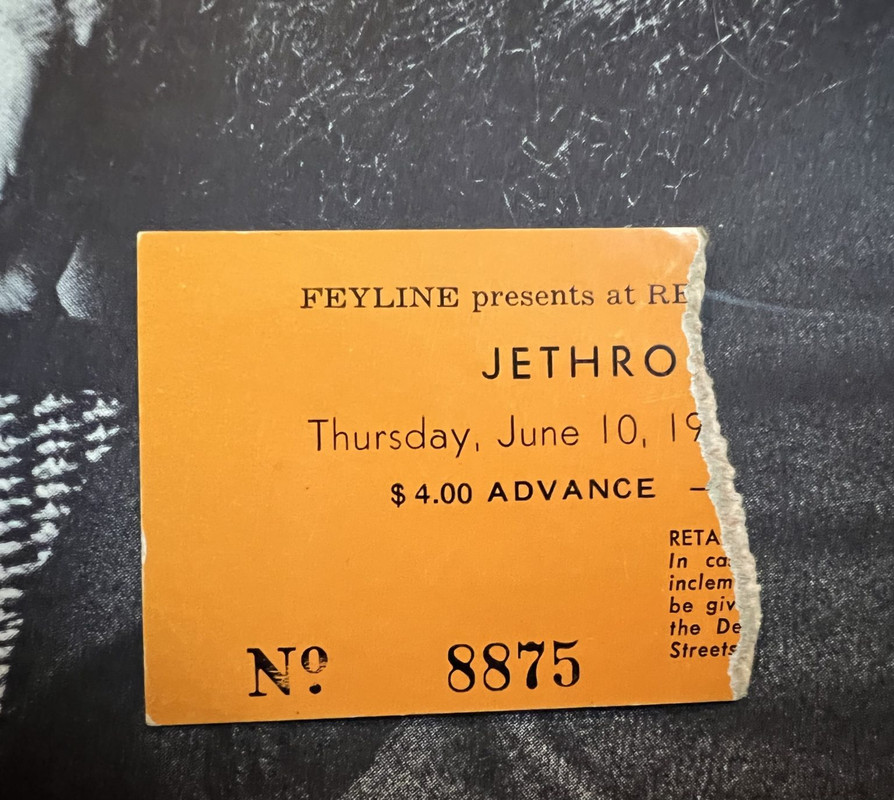

Special thanks to Todd Smith Special thanks to Todd Smith

Jethro Tull’s Colorado Connection By G. Brown LINK Jethro Tull was booked to open the summer concert season at Red Rocks on June 10, 1971.

In one of the most infamous events in Denver concert history, it resulted in a riot.

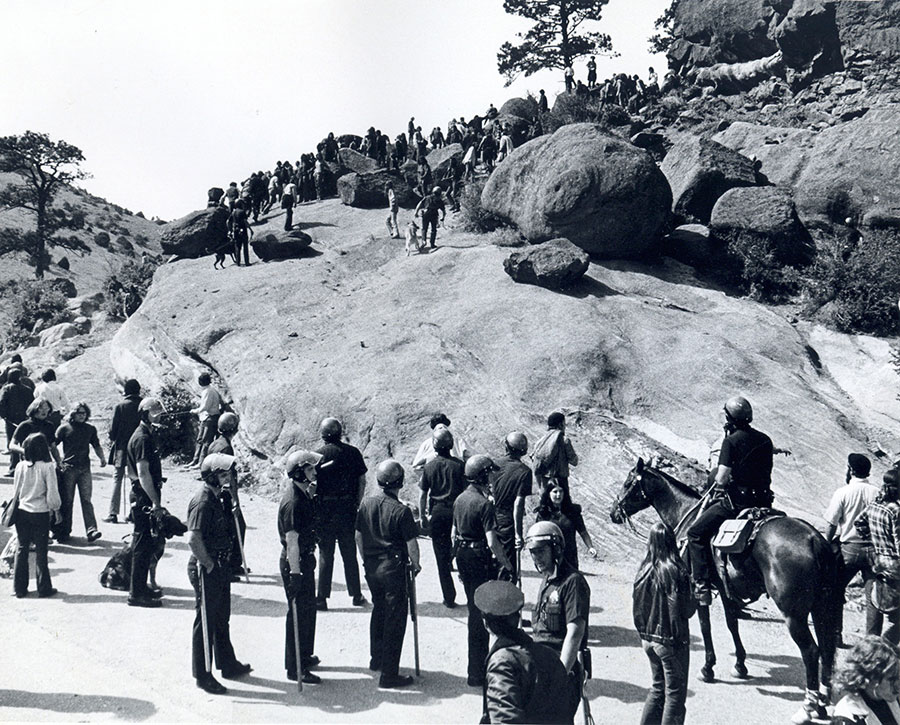

Rumors of impending unrest had surfaced in the days before the show. An estimated 2,000 fans who had

not been able to get tickets went peacefully to Red Rocks to situate themselves on the surrounding rocks

and hills to see and hear what they could, but there also was a militant faction determined to start trouble.

Extra police were called in at 3 p.m. to control gatecrashers. At 5:30, the police, under orders from

Lt. Jerry Kennedy, told the crowd they would be allowed to sit on the hill behind the theater

where they could hear the music, but not see the show.

The tumult started an hour before the concert was scheduled to begin, when a number of the “hill people”

started to climb over the outdoor venue’s back area in an attempt to get closer to the show;

they swarmed around the perimeter, walking over the bluffs and into the top parking lot.

The police had warned the crowd that tear gas would be thrown if they didn’t disperse,

feeling that the rough terrain would render any other way to maintain security impossible.

The first volley was dropped from a helicopter in the upper area.

Rather than acting as a deterrent, the tear gas incited the disorderly throng on to further acts of violence.

The crashers picked up bottles and rocks to use as ammunition against the police.

Adding to the problem, some of the gas began to fill the canyon-like shape of the amphitheatre, wafting

over the paying crowd and collecting on the stage at an alarming rate—a situation that

forced Livingston Taylor, the opening act, to make a hasty exit before finishing his set.

“This is supposed to be music!” he cried. “What’s going on here?”

While the police tended to the injuries outside the theater, the medical people attached to the

amphitheatre had more problems than they could handle. Two doctors who went into the audience to treat

severe injuries had their medical bags stolen and were rendered virtually helpless, while a small staff inside

the aid station bandaged cracked skulls and revived those who had been overcome by the varieties of tear gas.

That the concert went on at all was a tribute to the perseverance of the members of Jethro Tull.

“We were leaving our hotel to go up to the show when we received word that there was a problem,”

flute-playing frontman Ian Anderson said.

“We set off in our rented station wagons and were met by a police roadblock that tried to turn us back.

We said, ‘We’re the band,’ and we were told, ‘There’s not going to be a show, go away.’

We still had to make a fairly aggressive effort to get to the site—we wound up running a roadblock—

and when we got there, we realized there was trouble going on outside.

The police were trying to stop us from going to play—they felt that would make it worse.

I said, ‘Look, if you don’t let us go onstage, not only are there going to be 2,000 people outside rioting,

but 9,000 people inside are going to go crazy as well.’”

Reluctantly, the authorities allowed the British progressive rock band to proceed. Anderson wandered

on stage with tears in his eyes.  The other members were also weeping and gasping for breath— The other members were also weeping and gasping for breath—

keyboardist John Evan couldn’t see his piano through the tear gas.

Undaunted, Tull played anyway. Anderson surveyed the Denver police chopper hovering

in the distance dispensing periodic charges of tear gas at the rear of the assembly.

“Welcome to World War III,” he croaked, and the music, much of it from Tull’s album Aqualung,

went on for the next 80 minutes. Anderson was magnificent,

stalking the stage and playing his flute like a man possessed, despite the circumstances.

“The gas made life very difficult in the amphitheatre itself,” he said.

“The wind blew a cloud of gas over the audience to the stage. We had to stop several times.

I remember seeing babies being passed down through the crowd so they wouldn’t be affected by the gas.

It was a horrifiying sight. Happily, we were able to keep some sense of peaceful resolution with the audience.

By playing the show, we kept the lid on what could have become a very dangerous situation.”

The show at Red Rocks was one of drummer Barriemore Barlow’s first dates with the band.

“Having slightly upset the police on the circuitous way up there, we had to be careful going down again—

they saw us as the reason all this had happened,” Anderson said. “We were hiding under blankets in the

back of a rental station wagon, licking our wounds, lest the rather overly anxious local police decided to

encourage a fray. They shined their torches in the station wagon looking for the longhaired British rock band.

It was all a bit scary.  Our eyes were streaming and we were coughing. Our eyes were streaming and we were coughing.

Barrie turned to me and asked,  ‘Is it going to be like this every night?’” ‘Is it going to be like this every night?’”

In the wake of the riot, 28 persons, including four Denver policemen and three infants, were treated

at area hospitals for injuries suffered in the disturbances, ranging from broken bones to gas inhalation.

Dozens more—policemen, concertgoers and would-be gate crashers—were treated at the scene by

a volunteer medical team. Twenty people, including three juveniles, were arrested on charges ranging

from drunkenness to weapons violations and possession of narcotics. One parked car was overturned

and burned, and several other vehicles were reported damaged.

In the aftermath, the rest of the 1971 season—

Judy Collins, Burt Bacharach, Rod McKuen and the Vienna State Opera Ballet—was cancelled.

The debacle convinced Denver officials to ban rock events at Red Rocks—a ruling that held until 1975.

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Dec 13, 2019 7:34:41 GMT

Here's Why You Should Visit Red Rocks Park and Amphitheater for New Year'sBy Molly Harris | December 12, 2019 | 2:00pm www.pastemagazine.com/articles/2019/12/red-rocks-new-years-eve.htmlThough the first stage was built for concerts in 1906, the venue has become a mecca for artists of all kinds from opera singers to Sting. In fact, the only show that was not sold out during The Beatles 1964 tour was at Red Rocks-and it was the first rock concert the venue had seen. Later Jimi Hendrix, Jethro Tull and The Blues Brothers would play Red Rocks. Tull, however, left a five-year ban on rock concerts which resulted in a stint of performances by artists like Carole King, John Denver and Sonny & Cher.

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on May 28, 2022 5:43:06 GMT

www.boulderweekly.com/special-editions/red-rocks-the-music-the-myths-the-magic/Red Rocks: the music, the myths, the magicColorado music historian G. Brown sets the story straight about the beloved venue By Caitlin Rockett - May 26, 2022  As he sits down at a patio table at The Point Cafe, G. Brown slides a heavy tome in my direction: Red Rocks: The Concert Years. The book is a collection of more than 200 interviews the veteran Denver Post music journalist conducted over nearly three decades with an array of performers who’ve graced the landmark stage: Jerry Garcia, Dave Matthews, Bono, Paul McCartney. I flip through and stop at a picture of Icelandic polymath Bjork, who took the stage in May 2007, and wonder how fantastic that show must have been. “It was,” Brown says with a smile. Brown, who is the founding director of the Colorado Music Hall of Fame, is preparing to update his Red Rocks book. In celebration of the beginning of the summer—prime Red Rocks season—Brown took some time to talk about the history of the stunning amphitheater: the music, the myths, the magic. ---------------------------------- Jethro Tull: ‘Bungle in the Jungle’ becomes a Ruckus on the RocksThere’s no discussion of riots at Red Rocks without talking about Jethro Tull. The prog rock band was booked by storied Colorado agent Barry Fey, who was responsible for bringing the Grateful Dead, the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, Van Morrison, Jefferson Airplane, Frank Zappa and more to the Centennial State.  “I’ve always said what (Fey) did is worth something; how he did it I’ll never acquiesce to,” Brown says, referring to the “cartel methodology” that is still employed today to bring musicians to the area, including radius clauses that prevent musicians from playing at other venues within sometimes hundreds of miles. “But back in the ’70s, Denver was just a fly over city,” Brown says. “Kansas City was 600 miles one way, Salt Lake the other, and neither of those were developed markets, and (Fey) made Denver a stop.” Fey had orchestrated a show at Mile High Stadium several months before Woodstock in 1969, which devolved into tear-gas-soaked rioting. “So, one and done with that,” Brown says, “but it gave him the footing to start booking shows up in Red Rocks: Steve Miller Band; Hendrix famously played there opening for Vanilla Fudge.” In 1971, Fey booked Jethro Tull at the Morrison-based venue. “He should have booked Jethro Tull for two shows, of his own admission,” Brown says, because a large number of ticketless fans had showed up. “It was a different time: Music was free, cops are pigs, you know, the whole counterculture thing coming to roost in Colorado. There were a bunch of rabble rousers outside (Red Rocks), probably just a couple 100, but they decided they were gonna get in, and the cops used tear gas that the wind blew inside the venue where no one knew what was going on.” “Always a fan of that guy for what he did,” Brown says. “If he’d have just bagged it, there’d have been a riot that we’re still talking about. But they kept playing; (Anderson) gagged his way through a set like a whirling dervish madman and kept the show going on, otherwise it would have been really brutal.” The venue was eventually evacuated that evening, and rock music was banned from Red Rocks for a number of years. Of course Fey was instrumental in bringing that back: He sued the city and won the right to bring rock music back. In 1983, Fey promoted a show at Red Rocks for a little known Irish band called U2, who ended up filming a portion of Under the Blood Red Sky at that concert.

|

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Jun 28, 2024 0:11:18 GMT

Red Rocks: the music, the myths, the magicColorado music historian G. Brown sets the story straight about the beloved venue By Caitlin Rockett - May 26, 2022  As he sits down at a patio table at The Point Cafe, G. Brown slides a heavy tome in my direction: Red Rocks: The Concert Years. The book is a collection of more than 200 interviews the veteran Denver Post music journalist conducted over nearly three decades with an array of performers who’ve graced the landmark stage: Jerry Garcia, Dave Matthews, Bono, Paul McCartney. I flip through and stop at a picture of Icelandic polymath Bjork, who took the stage in May 2007, and wonder how fantastic that show must have been. “It was,” Brown says with a smile. Brown, who is the founding director of the Colorado Music Hall of Fame, is preparing to update his Red Rocks book. In celebration of the beginning of the summer—prime Red Rocks season—Brown took some time to talk about the history of the stunning amphitheater: the music, the myths, the magic. ---------------------------------- Jethro Tull: ‘Bungle in the Jungle’ becomes a Ruckus on the RocksThere’s no discussion of riots at Red Rocks without talking about Jethro Tull. The prog rock band was booked by storied Colorado agent Barry Fey, who was responsible for bringing the Grateful Dead, the Byrds, Buffalo Springfield, Van Morrison, Jefferson Airplane, Frank Zappa and more to the Centennial State.  “I’ve always said what (Fey) did is worth something; how he did it I’ll never acquiesce to,” Brown says, referring to the “cartel methodology” that is still employed today to bring musicians to the area, including radius clauses that prevent musicians from playing at other venues within sometimes hundreds of miles. “But back in the ’70s, Denver was just a fly over city,” Brown says. “Kansas City was 600 miles one way, Salt Lake the other, and neither of those were developed markets, and (Fey) made Denver a stop.” Fey had orchestrated a show at Mile High Stadium several months before Woodstock in 1969, which devolved into tear-gas-soaked rioting. “So, one and done with that,” Brown says, “but it gave him the footing to start booking shows up in Red Rocks: Steve Miller Band; Hendrix famously played there opening for Vanilla Fudge.” In 1971, Fey booked Jethro Tull at the Morrison-based venue. “He should have booked Jethro Tull for two shows, of his own admission,” Brown says, because a large number of ticketless fans had showed up. “It was a different time: Music was free, cops are pigs, you know, the whole counterculture thing coming to roost in Colorado. There were a bunch of rabble rousers outside (Red Rocks), probably just a couple 100, but they decided they were gonna get in, and the cops used tear gas that the wind blew inside the venue where no one knew what was going on.” “Always a fan of that guy for what he did,” Brown says. “If he’d have just bagged it, there’d have been a riot that we’re still talking about. But they kept playing; (Anderson) gagged his way through a set like a whirling dervish madman and kept the show going on, otherwise it would have been really brutal.” The venue was eventually evacuated that evening, and rock music was banned from Red Rocks for a number of years. Of course Fey was instrumental in bringing that back: He sued the city and won the right to bring rock music back. In 1983, Fey promoted a show at Red Rocks for a little known Irish band called U2, who ended up filming a portion of Under the Blood Red Sky at that concert.

|

|

Special thanks to Todd Smith

Special thanks to Todd Smith  The other members were also weeping and gasping for breath—

The other members were also weeping and gasping for breath—

But probably best in Humor, Games and Fun Thanks for sharing.

But probably best in Humor, Games and Fun Thanks for sharing.

. Anyone else? I know of one other

. Anyone else? I know of one other