|

|

Post by rredmond on Apr 8, 2020 22:22:17 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Apr 14, 2020 6:39:19 GMT

www.ultimate-guitar.com/Jethro Tull Leader Names Song 'That Got People's Knickers in Twist in Bible Belt of USA,' Reflects on Metallica Fiasco"I do not have faith. I believe in possibilities. I believe in probabilities. I have no time for certainties," Ian Anderson says. Posted 15 hours ago During a conversation with Louder Sound, Jethro Tull frontman Ian Anderson talked about religion, the 1989 Grammy's fiasco, and more. As widely reported, Tull won the '89 Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance Grammy with "Crest of a Knave," beating AC/DC's "Blow Up Your Video," Iggy Pop's "Cold Metal," Jane's Addiction's "Nothing's Shocking," and Metallica's "...And Justice for All." Asked about "My God," one of the songs from 1971's "Aqualung," Ian replied: "'My God' was the one that got people's knickers in a twist in the Bible Belt of the USA, mostly from worshippers who got the wrong message. But even back then, and certainly now, there are priests who say to me, 'I know what you were talking about with that song.' link

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Apr 15, 2020 6:26:53 GMT

JETHRO TULL’s IAN ANDERSON Talks METALLICA Easily one of the biggest upsets in rock n’ roll happened at the 1989 Grammy’s when JETHRO TULL upset METALLICA for Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance (Voice or Instrumental). Also included in the category were AC/DC, IGGY POP and JANE’S ADDICTION. During a recent interview with Classic Rock frontman IAN ANDERSON revealed to the publication his thoughts on the 1989 upset saying: “I didn’t think it was very likely that we would win the Grammy. And yes I was a little perplexed and amused when we were nominated in that category. Our record company told us, ‘Don’t bother coming to the Grammys. Metallica will win it for sure. My view is that we weren’t given the Grammy for being the best hard rock or metal act, we were given it for being a bunch of nice guys who’d never won a Grammy before, And there wasn’t an award for the world’s best one-legged flute player.”gnrcentral.com/2020/04/14/shockingly-good-alice-in-chains-alanis-morissette-mash-up-surfaces-online/ |

|

|

|

Post by bunkerfan on Apr 15, 2020 6:57:32 GMT

JETHRO TULL’s IAN ANDERSON Talks METALLICA Easily one of the biggest upsets in rock n’ roll happened at the 1989 Grammy’s when JETHRO TULL upset METALLICA for Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance (Voice or Instrumental). Also included in the category were AC/DC, IGGY POP and JANE’S ADDICTION. During a recent interview with Classic Rock frontman IAN ANDERSON revealed to the publication his thoughts on the 1989 upset saying: “I didn’t think it was very likely that we would win the Grammy. And yes I was a little perplexed and amused when we were nominated in that category. Our record company told us, ‘Don’t bother coming to the Grammys. Metallica will win it for sure. My view is that we weren’t given the Grammy for being the best hard rock or metal act, we were given it for being a bunch of nice guys who’d never won a Grammy before, And there wasn’t an award for the world’s best one-legged flute player.”gnrcentral.com/2020/04/14/shockingly-good-alice-in-chains-alanis-morissette-mash-up-surfaces-online/  |

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Apr 15, 2020 11:19:16 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Apr 25, 2020 13:27:54 GMT

Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull on population

945 views•Apr 22, 2020

Population Matters

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on May 20, 2020 6:21:29 GMT

www.talkers.com/2020/05/19/tuesday-may-19-2020/  Rock Legend Ian Anderson Is This Week’s Guest on Harrison Podcast. Rock Legend Ian Anderson Is This Week’s Guest on Harrison Podcast. One of the most respected singers, songwriters, and musicians of the album and classic rock era, Ian Anderson, is this week’s guest on the award-winning PodcastOne series, “The Michael Harrison Interview.” Anderson is the front man, founder, organizer, and driving force behind the historic British progressive rock group, Jethro Tull. Harrison caught up with Anderson who is quarantining at his home in the UK. They engage in a deep-dive conversation about a broad range of subjects including music, politics, COVID-19, and wildlife conservation. Harrison states, “In addition to being a unique and supremely talented musician, Ian is a scholarly man with a golden tongue who can hold his own among the best ‘talkers’ in the English-speaking world. Having long-managed his own case of the breathing disorder, COPD, he is extremely educated and opinionated about everything having to do with the coronavirus – which he amply shares in this interview.” Anderson sings and plays flute on a new recording by Hungarian-born German rock star Leslie Mandoki titled “#We Say, Thank You” (check it out on YouTube) which pays tribute to the frontline heroes of the COVID-19 era and chastises those speculators who are exploiting it for financial gain. To listen to this fascinating podcast in its entirety, please click here or click on the player box marked “The Michael Harrison Interview” located in the right-hand column on every page of Talkers.com. www.podcastone.com/the-michael-harrison-interview

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Jul 4, 2020 6:23:54 GMT

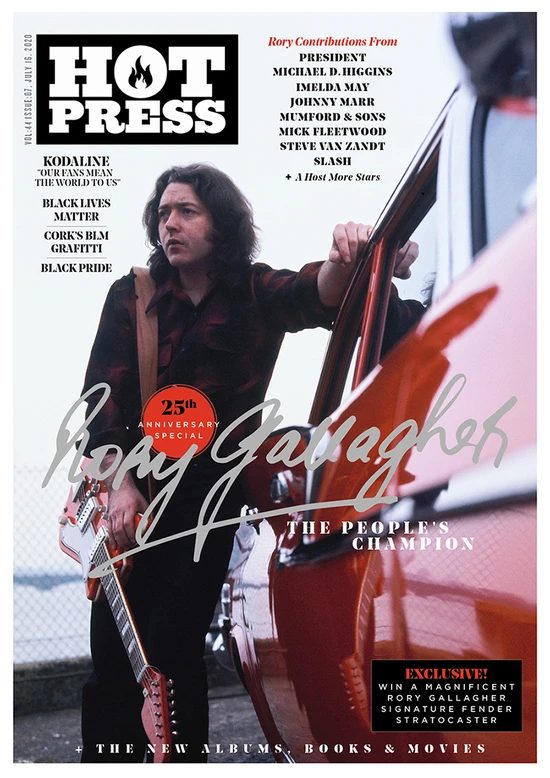

www.hotpress.com/03 JUL 20 Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson on Rory Gallagher: "He could raise the roof or hush the hubbub of the bar" BY: IAN ANDERSON Ian Anderson shares his reflections on Rory Gallagher's legacy, as part of our special 25th anniversary tribute to the legendary Irish guitarist. Best known as the lead singer, flautist and acoustic guitarist with Jethro Tull, one of the most successful progressive rock bands in history, Ian Anderson has also released several solo albums. * * * * * Jethro Tull and Rory worked together from his earliest days with Taste at the Marquee Club, London in 1968 and then on tour stadiums in the USA in the 1970s and festivals in Europe in the 1980s. The thing which set Rory apart from the other blues bands and artists of the early days was – simply – energy. Rory had a good handle on the structure and traditions of black American blues but, rather than slavishly try to recreate the BB King licks and the vocal stylings of Muddy Waters et al, Rory went his own way. There was more angry white Irish boy with a half-empty Jameson in the Gallagher vocal delivery than Chicago bluesman with Jack Daniels. A master of dynamics, Rory could raise the roof or hush the hubbub of the bar with confident control. I always felt that Rory was the prototype for the early Joe Bonamassa – another purveyor of raw energy when Joe arrived on the world music scene in 1981. Advertisement Above all, my memories of Rory, the man, are marked by his Irish identity. Those roots seemed all-important to him and that fierce national identity – politics and all – frequently came into conversation. I have no doubt that our paths would still cross, both on-stage and back-stage to this day, but for his sad passing at the mere age of 47. The special Rory Gallagher 25th Anniversary Issue of Hot Press is out now – featuring reflections on Rory's legacy from President Michael D. Higgins, Imelda May, Johnny Marr, Mumford & Sons, Mick Fleetwood, Steve Van Zandt, Slash and many more. Pick up your copy in shops now, or order online below:  www.hotpress.com/music/jethro-tulls-ian-anderson-on-rory-gallagher-he-could-raise-the-roof-or-hush-the-hubbub-of-the-bar-22821459 www.hotpress.com/music/jethro-tulls-ian-anderson-on-rory-gallagher-he-could-raise-the-roof-or-hush-the-hubbub-of-the-bar-22821459

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Jul 17, 2020 6:44:06 GMT

www.rockcellarmagazine.com/Rockers Recall The Most Impressive Live Acts They’ve Seen, Part 3 (Ian Anderson, Ricky Phillips & James Young of Styx, More) BY KEN SHARP ON JULY 16, 2020 With a return to live concerts unlikely for 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic, join us for the next best thing, more recollections from noted rock luminaries queried about their favorite live acts witnessed firsthand — this follows Part 2 of the series. Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull): Well, it would always be a toss-up between the Rolling Stones – mainly for the energy and commitment of Mick Jagger, and Led Zeppelin who during their time-gone-by and more recently, as we all know, captured the essence of rock, blues, folk and world music in a way which preceded most. The vocal gymnastics of Robert Plant and the spirited, innovative guitar of Jimmy Page have probably never been equaled. No need for elaborate stage sets, backing musicians, taped or sampled effects; just the four guys and their music, played quite loudly but always with control and finesse. I think the Zeps win out for me, especially since their music grew from the basic blues riff approach through to encompass many more stylistic influences. And their recent reunion concert did much to dispel the critics’ trepidation that they couldn’t possibly come back from the twilight zone. link

|

|

|

|

Post by steelmonkey on Jul 18, 2020 19:22:54 GMT

It would be great to force feed Ian the best of the 80's which, beyond stated appreciation for The Stranglers and The Ramones, he seems to have sat out. I can't imagine him not finding a lot to like among acts like Elvis Costello, The Psychedelic Furs, Echo and the Bunnymen and Patti Smith. Maybe no Zep nor Stones quality concerts in terms of sheer power but a lot of energy, talent and sincerity.

|

|

|

|

Post by steelmonkey on Jul 18, 2020 19:23:57 GMT

Or better yet..a Clockwork Orange style forced consumption of Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds at their best.

|

|

eridom

Prentice Jack

Posts: 31

|

Post by eridom on Jul 19, 2020 4:11:27 GMT

It would be great to force feed Ian the best of the 80's which, beyond stated appreciation for The Stranglers and The Ramones, he seems to have sat out. I can't imagine him not finding a lot to like among acts like Elvis Costello, The Psychedelic Furs, Echo and the Bunnymen and Patti Smith. Maybe no Zep nor Stones quality concerts in terms of sheer power but a lot of energy, talent and sincerity. Elvis Costello’s best albums were released in the 70s |

|

|

|

Post by steelmonkey on Jul 19, 2020 22:32:18 GMT

I love Elvis Costello's second wave...Spike, Mighty Like a Rose, All this useless beauty.

|

|

eridom

Prentice Jack

Posts: 31

|

Post by eridom on Jul 20, 2020 1:50:41 GMT

I love Elvis Costello's second wave...Spike, Mighty Like a Rose, All this useless beauty. No doubt but when I think of Elvis I don’t think of the 80s. |

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Jul 21, 2020 1:24:58 GMT

lavozdelsur.es  LINK LINK

Home / Culture / Music / Gypsy Rock / Ian Anderson:

"I am attracted to the parts of Spain that have a connection to the sea"Gypsy Rock interviews the legendary guitarist and flutist of the British band Jethro Tull The British Jethro Tull have a reputation for being, after the Rolling Stones, the longest- The British Jethro Tull have a reputation for being, after the Rolling Stones, the longest-

running group in pop history. Its only permanent member, in five decades of activity,

is the leader, flutist and singer Ian Scott Anderson (Dunfermline, 1947).

See if we are older, Ian, who rejected the legendary Woodstock in 1969, with the excuse that the

band was not yet oiled. It is also rumored that drugs and free love were not a stew on his palate ...

Anderson was never a hippie, and insists that today's public is very different from then:

"Today they shower more often.They are less idealistic, perhaps, but more informed and cultivated.

But the important thing is that they shower more often. And, at least in recent times, they wash

their hands much more often too! Hopefully that will continue for a long time. "

We talked to Ian Anderson about very present pasts. The entire interview is carried out in writing

and the frontman shows us, with some of his turns of phrase,

why he is one of the most esteemed lyricists in progressive rock.

Feeling the cliche very much, we began by expressing our admiration for his generation:

for the quality and quantity of bands that roamed the world, and especially the United Kingdom,

in the 1960s and 1970s. The enthusiasm is shared: “It is like the landing on the moon.

Like the advent of impressionism. Like the work of climate scientists and conservationists today.

They were all special in and for their time. These great social adventures happen of course more

than once, but the first time is a great expedition into the unknown.

There are no easy precedents to follow. There are no previous models to emulate. "

And yet Anderson is by no means the typical rocker of the 70s.

To begin with, because of the unusualness of his instrument:

"I am a self-taught rock musician and I only see the flute as a solo voice to compete with

the electric guitar." In his time there were no easy precedents for a rock flutist either, and

even today many music lovers fall ashamed if they ask us to quote someone else. Anderson

is inspired by "James Galway and Andrea Griminelli from the world of classical music,

Matt Molloy in Irish folk music, Hariprasad Chaurasia ... But they all play differently than mine."

Another singularity of the flutist: he always listened to little music. He was never a huge fan

of club-hopping , even in the days when Pink Floyd played at the Marquee.

In his first interviews, he did not succeed in unraveling the influences of his hard and bucolic rock.

In fact, it is surprising to discover which genres their selective filters manage to pass:

"I have always been seduced by Indian classical music,

since I started eating Indian food in the late sixties."

Hariprasad Chaurasia and Anoushka Shankar are some of his reference artists,

and he has had the privilege of sharing the stage with both of them:

"Steep learning curve for a British boy with white skin and blandiblu legs!"

Either because of his drug rejection or because of his Hindu diet, the point is that Jethro Tull

turned out to be a surprisingly solid project, or, to put it in Tullian words , "thick as a brick."

Anderson has released over 30 studio albums and toured almost every year between 1969

and 2020; We are confident that when restrictions on music events are lifted, you will be

the first to hit the road. Meanwhile, along with his veteran collaborator Leslie Mandoki,

he dedicates a heartfelt song to doctors, nurses, supermarket cashiers,

and others who play the guy every day in the current pandemic: "#WeSayThankYou."

We asked him about some hobbies that help him to confine himself:

"Photography, the off-road bicycle and shooting ... but only to things without a face."

He recognizes that, when he is not doing dozens of concerts around the world,

he is "a seventy-year-old man who does not leave the house"; in his case,

from his Wiltshire country house, where he cultivates some of his wild hobbies.

“I read, but especially when I travel. I am currently reading a philosophical

and scientific book by Dr. Bruce Lipton, The Biology of Belief . "

Like most musicians on the planet, Anderson has had to cancel or postpone his scheduled

concerts in recent months. This supposes an abrupt stop in a routine of almost one hundred

shows a year: we warn that the geography of their annual tours can cause dizziness.

Spain, for one reason or another, is usually well represented in them. We cannot help but ask

if any national fan has explained to him that the publication of the album Aqualung (1971)

was delayed in Spain until 1975, the year Franco died, and even then the song “Locomotive Breath”

—considered “obscene” was replaced. - for "Glory Row".

(Instead, the atheistic hymn "My God" passed the sieve: perhaps the censor had too much culture

to maim that day.) None of this seems to surprise him:

“Censorship and criticism by the governments of various nations were not uncommon back then.

Often political and religious dogma has attempted to control the art and expression of its time.

But that's part of the fun of being an opposition writer, painter, photographer, or even politician.

We all like to have something to fight against, that makes us think and work harder. ”

In any case, we have done our homework: today Spain even has annual Tullian conventions .

The Scotsman tries to visit us every year: “I suppose I am especially attracted to the parts of

Spain that have a connection to the sea and the resulting trade, exploration and romantic history.

Architecture and a multitude of influences, from Christianity to Islam and Judaism,

have shaped the past. The bustle of Barcelona and the traditions of Jerez, Cádiz, Seville and

Malaga are more attractive to me than the beach vacation destinations

or the British retirement enclaves of the Coasts ”.

Pepe the Scotsman.

One of the last Jethro Tull concerts in our country took place at the Tío Pepe Festival in

Jerez de la Frontera. Anderson had already visited Jerez in 1998.

Last summer, the composer of Heavy Horses took the opportunity to satisfy his family's curiosity

about horse riding and horses. We told him about the extraordinary presence of men with kilt

at the Jerez Fair since the 1950s, and we sent him some photos of the proverbial Pepe el Escocés,

a flamboyant character in a skirt who was, for a couple of decades, an obligatory presence at

the Andalusian April Fairs (some said he was Dutch, in the end it turns out he was French).

We discussed the secret connection that seems to exist between places as disparate as

the Scottish Highlands and our Lower Andalusia. Anderson - who in recent years

has also visited Córdoba, Málaga, Fuengirola and Granada - ventures a hypothesis:

“Could it be that the connection between Scotland and Jerez is the widespread use,

then and now, of old barrels of sherry transported to the Scottish Highlands and isles for use in

the maturation of Scotch whiskey? And finally, those tattered , old, unusable sherry / whiskey

casks are pulverized to make sawdust and burned in ovens to smoke Scottish salmon.

Now that's recycling!"

And that Scottish salmon, smoked on ash from barrels that left Jerez, returned to the groceries

of the Andalusian cities as a luxury product on the appointed dates of Christmas, closing the

ecological cycle. Our wineries sent them wine and they, revelers, to our fairs. Fortunately,

Anderson shows us that there is another way to be Scottish, and another way to be a rock legend.

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Jul 27, 2020 6:22:49 GMT

fox5sandiego.com/Is The Movie A Remake, Homage, or Plagiarism? Groundhog Day vs Palm Springsby: Josh Board Posted: Jul 26, 2020 When I interviewed Ian Anderson, the singer/flutist of Jethro Tull, he talked about The Eagles stealing a riff from one of their songs. He also told me about how in the movie This is Spinal Tap, the character Nigel Tuffnel (Harry Shearer), was taken from a fictional character he had on his album “A Passion Play.” He once had Shearer come up onstage at a concert in L.A. and he sprung that on him. Shearer had no clue what he was talking about, saying he just came up with that name on his own. Is that a coincidence? It seems unlikely. link

|

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Aug 15, 2020 20:08:07 GMT

Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull) Dec 11, 1984 Sydney Today TV show

|

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Aug 28, 2020 1:12:11 GMT

2019 Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull Radio Interview

|

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Sept 4, 2020 1:07:08 GMT

Ian Anderson On TAAB 2

4 videos 1,683 views Last updated on Mar 14, 2012

|

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Sept 22, 2020 0:21:10 GMT

Ian Anderson, the frontman of Jethro Tull, on the occasion of the postponement

of the band's concert in Technopolis, which was scheduled for 12/9,

spoke exclusively to Red 96.3 and Christos Papadas.

|

|

|

|

Post by Jack -A- Lynn on Sept 22, 2020 14:44:36 GMT

Oh thanks  I really don't have a way with watching news. Especially lately i'm not in such good frame of mind... Thank you do this for us. |

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Sept 23, 2020 2:03:45 GMT

Oh thanks  I really don't have a way with watching news. Especially lately i'm not in such good frame of mind... Thank you do this for us.  GREECE ROCKS with TULL !!! GREECE ROCKS with TULL !!!   |

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Oct 3, 2020 11:43:58 GMT

Missed this due to my hospitalization  www.rollingstone.com/ www.rollingstone.com/AUGUST 27, 2020 8:42AM ET Ian Anderson, Jethro Tull Pen Open Letter on Covid-19 to U.K. GovernmentAnderson muses on how outdoor and indoor live performances could be carried on safely during pandemic  Ian Anderson and his band Jethro Tull have signed an open letter to the U.K. government outlining the realities of the Covid-19 crisis for musicians and suggesting possible solutions for how to bring back live music. In the preface to his letter, Anderson notes that he had privately sent it to U.K. Culture Secretary Oliver Dowden on July 1st, and again to Minister for Digital and Culture Caroline Dinenage on August 12th, but had never received a response from either of them. “Hard to make any progress with this muddled, uninformed and lackluster U.K. government,” he writes. “I am so sad for all of us in this now extremely precarious industry of arts and entertainment and sad for our audiences too.” Anderson then explains the scientifically proven safety concerns with performing music live in either outdoor or indoor venues, noting that the spread of the novel coronavirus through aerosol droplets has been found to be more likely than surface contamination, which can be avoided through proper cleaning procedures. The main challenge facing indoor venues, Anderson notes, is that they are typically cooled, dry spaces thanks to A/C units blowing air throughout the space — a perfect home for viruses. With that said, he believes that outdoor concerts are largely safe for the moment as long as all attendees wear masks — “at least a 50p 3-layer surgical mask, not a flimsy single layer homemade cosmetic face covering” — and keep a suitable social distance apart through seating or otherwise. He even demonstrates how outdoor spaces or even very large indoor venues can retain 70% capacity, as opposed to only 35%, by keeping seats spaced one meter apart and allowing household groups to sit closer together, as Anderson did at his recent U.K. cathedral show. Anderson admits that creating a safe protocol for indoor performances will be much more difficult and that a one-size-fits-all scenario would be ineffective. He writes: “I suggest that environmental health assessments are carried out for theatres and concert halls and they can be granted (or not granted) an interim COVID license to operate with restricted seating and all the other obvious sanitary and entry/exit/toilet protocols in place. That will take many weeks to carry out but I really think that we have, realistically, until next spring to do this when, hopefully, infection rates are down to a safer level.” Indoor performances have returned to certain parts of Europe, such as Germany, where scientists have tentatively begun experimenting with different concert scenarios to see how Covid-19 might be spread in a live music setting. Much is still unknown about the dangers of Covid-19 in different types of mass gatherings, but scientific evidence has backed Anderson’s claim that the virus is transmitted primarily through aerosols. link |

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Oct 10, 2020 0:40:08 GMT

Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull Interview on 101.5 KOCI Emily Morenz  Here is an interview I did with Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull on Here is an interview I did with Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull on

"Emo's Rock 'N' Roll Magic Show" on 101.5 KOCI FM back in July 2019.

This man is a hoot! We got to hang out with a bit backstage as well!

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Dec 11, 2020 7:29:14 GMT

www.ultimate-guitar.com/Jethro Tull Leader Recalls Anger After Band's Bassist Died Aged 28, Talks Group's Keyboardist Coming Out as Transgender Aged 61"I could have done more to confront John and steer him back." Posted April 09, 2020 During a conversation with Classic Rock Magazine, Jethro Tull frontman Ian Anderson looked back on the band's late-'70s lineup, particularly focusing on keyboardist David Palmer, now known as Dee Palmer, and the late bassist John Glascock. John joined the band in 1975, making his studio debut with the group on 1976's "Too Old to Rock N' Roll: Too Young to Die!"; Palmer became the Tull keyboardist in 1977 after collaborating with the group for a decade as an arranger, making his studio debut the same year on "Songs from the Wood." Apart from Ian, the rest of the group's lineup at the time also featured longtime JT guitarist Martin Barre, keyboardist John Evan, and drummer Barriemore Barlow. The lineup dissolved soon after Glascock died in November 1979 due to a congenital heart valve defect worsened by an infection caused by an abscessed tooth. He was 28 years old. Before the lineup ended, the guys released "Heavy Horses" in 1978 and "Stormwatch" in 1979. After the interviewer said about Glascock, "It was said that he'd damaged his health with drink and drugs - and that you'd threatened to kick him out of the band in an effort to straighten him out. What's the truth in that?", Anderson replied: "John was always a bit of a party guy from the get-go. He wasn't a wildman. He was an easygoing, nice guy, a benign drunk. And I've known people who were not that way. John was never fired from the band. "He was just told by me: 'You've got to stop and get yourself fixed, and come back when you're well.' When we stepped away from day-to-day contact with him it could have gone either way. "I hope he knew his job was waiting for him if he could make it back. But he didn't, and that was a great sadness that we had." How did that affect you emotionally? "It made me angry with him. It made me angry with myself. I could have done more to confront John and steer him back. "We all could have tried harder to make him understand that this really wasn't a great way of living his life, and his job depended on sorting himself out. "But one will never know if his demise was due to the failure of the heart surgery he had, or to what degree it might have been aggravated by his lifestyle." Within a year of John's death, Barriemore Barlow and David Palmer had left the band. These were old friends of yours. Before Tull, Barlow had played alongside you in The Blades in the early '60s, and Palmer had worked with Tull since 1968. And in all those years, Palmer had kept a secret from you, a secret that was finally revealed in 1998, when Palmer came out as transgender, renaming herself Dee. "I remember it well. I called him - and I'll say ‘him' because at that point, as far as I knew, he was David Palmer - to say: 'I've got a bit of a problem here with some journalists hanging around my house insisting that I'm cross-dressing and that I'm planning to have a sex change.' "I laughed it off and said: 'Where could they have got this story from?' At which point David said: 'Ah, Ian, I'm glad you called...' And I quote him quite precisely here: 'There's something I've been wanting to get off my increasingly ample chest...'" Do you think there were clues that you'd missed? "There were some signs. The clothes that David was wearing in the late '70s seemed a little odd, a little ambiguous. Somebody had said: 'It looks like there's a bra strap under his shirt.' "But in all those years, he and I never had a conversation about the issues he had as a child, growing up in an uncomfortable way. "That conversation came much later on, after the gender reassignment - a complete transformation. When I saw her then, it was quite difficult for both of us. "It was difficult for a lot of people who knew the old David Palme because he had seemed in many ways like the last person in the world who would go in that direction. "He was kind of a man's man. He smoked a pipe and spoke with a deep voice. David was in his sixties when he made his decision. It was a very brave thing to do."

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Dec 15, 2020 7:21:48 GMT

www.ocregister.com/10 Jethro Tull stories Ian Anderson told us before band’s Southern California shows to celebrate 50th anniversaryOpening for Led Zeppelin, skipping Woodstock and how Eric Clapton influenced him By PETER LARSEN | plarsen@scng.com | Orange County Register PUBLISHED: June 26, 2019 at 8:20 a.m. | UPDATED: June 26, 2019 at 8:20 a.m.Ian Anderson is a natural-born storyteller, but spend five decades as the flute-playing, occasionally cod-piece-wearing frontman of Jethro Tull, and yeah, you’ll have some stories to tell. Anderson, who called from his office in England recently to talk about his upcoming shows in Southern California, is continuing the celebration of Jethro Tull’s 50th anniversary, which kicked off last year – 50 years after the band’s first gigs at Marquee Club in London – and continue this year to celebrate 50 years since Tull made its live debut in the United States. “We did three U.S. tours in 1969,” Anderson says. “Early spring, I think July, and then again later in the year.” “As a child growing up in the U.K. shortly after the end of World War II, we were brought up on a diet of all things American,” he says. “American comics, American TV programs, if you were lucky enough to have a television in those days back in the U.K. “And so we grew up with a steady diet, I suppose, of appreciation and envy of this incredibly brash and culturally exciting world.” The tour billed as Ian Anderson’s 50 Years of Jethro Tull – he’s been the sole original member since Martin Barre left in 2012 – plays the Fantasy Springs Resort Casino on July 5 and FivePoint Amphitheatre in Irvine on July 6. Since Anderson, 71, is so good at spinning a tale, we decided to get out of the way and let him talk about everything from why Jethro Tull decided to pass on playing Woodstock to how Anderson ended up a rock-and-roll flautist in the first place – Eric Clapton is responsible for it, he says. But we’ll start with their very first U.S. shows when Tull opened for another British band. 1) Opening for Led Zeppelin: “We were in that invidious position of going on before one of the world’s most loved and appreciated bands, musically speaking. So it was a tough opening act to do, but I think generally speaking we did OK. The first couple of times we had 35 minutes to try and show that we were not complete idiots, and we obviously managed to do OK since we were invited to do it again and again.” 2) Taking a Page from Jimmy: “The Zeppelins, they were a good act to open for because you really had to learn, and you could learn from them a lot of useful tricks about stage presentation and dynamics. Generally speaking on a good night they were the best band in the world,” says Anderson. “There was always something fresh to learn from watching them, except for me watching Robert Plant because he was in a class of his own. I couldn’t learn anything from him because I couldn’t dream of doing that kind of performance, either the macho bare-chested kind of strutting or the incredible operatic range of his voice. I learned perhaps more from the way Jimmy Page presented himself, his little bit of theatrical stuff, bowing his guitar with a violin bow, for example.” 3) Playing Newport Jazz ’69: “The jazz festival was a fairly staid affair, and not really a great venue for Jethro Tull. It had a night that was dedicated more to blues, well, non-folky, more electric music, but I’m not sure for most of the audience we were a welcome component of the lineup or not. But I do remember (jazz multi-instrumentalist Rahsaan) Roland Kirk coming backstage and saying hello to because he’d heard I’d recorded music by him on our first album. It meant a lot to me that he sought me out.” 4) Skipping Woodstock: “I said, ‘What’s the sort of shape of this festival, what kind of people are going to be there?’ (Our manager) said, ‘I think it’s going to all be naked hippies taking drugs.’ So I said, ‘Well, I think actually I can be washing my hair that day,’ because back then I used to have quite a lot of it so it was a plausible excuse.’ I didn’t feel it was the right thing for Jethro Tull so early in our career to be fixed with that label of being a hippie band.” 5) Coming to America: “The American boy (at Anderson’s primary school) used to give me his American comics once he read them, so I grew up knowing about all the things that were on the back page, all the sort of postal ads that you could off and get anything from a plastic Elvis ukulele to a ‘Wynn’ bicycle. And BB guns, which fascinated me. Of course, we’d seen lots of cowboy movies — that rather Midwestern kind of more rural America was the America that I thought was what it was until in my mid-teenage years when I was listening to jazz and blues. Then it was the upper Midwest — the Chicago thing became my sort of vague awareness of American, and through jazz musicians a little bit of New York.” 6) Messing with Texas: “The thing that impacted on me most of all about the USA was you couldn’t just talk about ‘the USA’ in the way that you might talk about Germany or Switzerland or Spain. Because America’s like five or six different countries in terms of social and cultural differences, as well as in terms of topography and the physical geography of that big chunk of a continent,” says Anderson. “You realize just how enormous and how diverse it was, and how different people were in their behavior and perhaps their acceptance of people like us. We were warned, be careful when you go to Texas. And I do remember stopping once in a station wagon when we were traveling, we got out at some gas station, and we suddenly realized that we better get back in the car and get out of there very, very quickly because some very threatening guys were coming down to take us to task for having trousers that were too tight and long hair and sort of Carnaby Street clothes.” 7) Learning from Eric Clapton: “Like many of my peers I was a teenager who fantasized about being a guitar player, and perhaps a singer. And so my first two or three years were doing that. But then a bad thing happened. I bought an album by John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, featuring a new guitar player by the name of Eric Clapton, and I thought, ‘I think I better find something else to play.’ And so in the summer of 1967, I traded in my Fender Strat guitar.” 8) Selling a special guitar: “Being a 1960s vintage Strat, apart from being owned by me it was also previously owned by Lemmy Kilmister — then from Rev Black and the Rocking Vicars — but of course more famous for Motörhead. He’d owned it before me, it’s a vintage Strat, so this guitar for sure would have to be worth £30,000, £40,000 today,” says Anderson. “But I traded it in for a £30 Shure Unidyne III microphone, which I rather coveted, it looked rather sexy. And for the balance — What do I want? — I saw this shiny flute hanging on the wall (for £30 pounds). So for £60 I got myself a real made-in-Chicago microphone and a student flute I couldn’t play.” 9) Figuring out the flute: “I had a go at it; I couldn’t get a note out of it. About four months later, December of ’67, I thought I’d give another try, see if I could get a noise out of it, and all of a sudden a note popped out of it: ‘Ooh, that’s how you do it!’ And then I got another note. Soon I had five notes. And I had the pentatonic blues scale, and I could play solos and riffs,” says Anderson. “A few days later I was playing it on stage in the early days of Jethro Tull in the Marquee Club, and people noticed. ‘Oh, there’s a band that plays the blues but they’ve got a flute player?’ And that, in marketing terms, was a point of difference in good marketing and promotion. People noticed it because we were different than other bands.” 10) Going on fifty years: “It stood us in good stead over the years, and over the years I’ve come to really enjoy the flute much more than when I started. I can do a lot of stuff that I couldn’t do before, but I can still do the stuff I did in the first week that I was playing it. That way of playing never leaves you. I can do that in my sleep, which sometimes I do. It keeps me awake at night.”

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Dec 15, 2020 9:36:03 GMT

www.rockcellarmagazine.com/Behind the Curtain: Interviewing Jethro Tull’s Ian Anderson in 1975STEVE ROSEN ON DECEMBER 14, 2020 For his latest Behind the Curtain entry, rock journalist Steve Rosen recalls his admiration of Jethro Tull and Ian Anderson — and the particular challenge that interviewing Anderson in 1975 presented. OK, I’m just going to come out right here at the beginning and say it so there’s no confusion. I am going to clear the air, let you know where I stand: I think Jethro Tull is one of the most inventive, innovative and essential bands in all of rock. Ever. In my listing of the 10 or 20 greatest bands of all time, I would write down their name. So have I stirred the pot? Rattled some bones? Are you in the throes of uncontrollable laughter, your razz meters turned to 11? Are you right now wishing you could reach through your monitor (or laptop) so you could grab me by the collar, slap me silly and ridicule me with taunts of, “You moron. You suck. Die.” You done? Got that out of your system? Doubtful I can change your mind, so I won’t even try. I can tell you what I know about them, from spending some time with Tull figurehead Ian Anderson and longtime guitarist Martin Barre, why I think they’re so remarkable and why they’ve been everybody’s favorite punching bag for about the last 12 eons. For starters, they were pegged as a prog band from the get-go and I always thought that was wrong. “Everybody” hates prog bands, right? Unless you were a prog person, you would never listen to Yes, King Crimson, Emerson, Lake & Palmer or Genesis — but you’d sure as hell listen to Peter Gabriel and Phil Collins, so what’s up with that? In that context, Jethro Tull had a strike against them before they even stepped up to the plate. They actually began as a blues band, emerging from that London scene where bands like Fleetwood Mac, Humble Pie, Free, Ten Years After, Savoy Brown and others were shaking things up. But they quickly shed those blues shoes after just one album [This Was, their debut] and turned to a much more melodic, hard rock sound with their second record titled Stand Up, which walked its way to number one in the UK charts. Oh, ye of little faith. Was it a progressive rock album? I don’t think so. Big electric guitars, some bluesy stuff, some folksy acoustic elements but prog? Hardly. So why the tag? The flute, man. That long metal tube Ian Anderson was blowing on all the time. Some stupid, narrow-minded critic, some simpleton who doesn’t know $h1t about music or songwriting, arrangements, or textures, mistakenly calls Tull’s music “progressive” because he sees some stringy-haired dude dancing around in a trench coat, perched on one leg playing a classical instrument and since he can’t call the band classical he calls them prog. There was nothing that complex about the music on Stand Up. There weren’t weird time signatures or complex, lengthy, rambling, avant-garde instrumental sections. Those were four-minute songs, melodic, simple to digest. The “prog” tag stuck like some ignominious badge of dishonor, Tull were doomed from the start. It didn’t matter that Benefit and Aqualung, their third and fourth albums, were insanely amazing records and sold unbelievably well because the damage had already been done: Jethro Tull was labeled a prog band and well, that was the end of the story. At least that’s what I think. If Peter Gabriel or Sting or some hip, au courant band of the time had written and recorded those songs, everybody would be hailing those artists as trendsetters, world class songwriters. But Jethro Tull performed those songs and Ian Anderson, a kind of strange cat who played the flute wrote and sang them and for some reason neither the band nor singer was hip and if you dug the band you yourself weren’t hip. In fact, if you liked Tull you were persona non grata. I am persona non grata and proud of it. So, I was tickled to have the chance to sit and interview Anderson during their 1975 Minstrel in the Gallery Tour. No, I was honored. I thought he was one of the best songwriters ever and as you now know I love the band and to have that opportunity of meeting and talking to him was f**king cool. I had flown out to one of the band’s gigs — I can’t remember where — and in preparation I had listened to all the seven previously-released records, though all I really cared about were Stand Up, Benefit and Aqualung, which were without question the high-water marks. (Honestly, just so you think I’m not some sycophantic super-fan who loved everything they did, I didn’t like the other albums very much). Arriving at the hotel in the morning, I was told I’d speak with Ian that same afternoon. As the tour manager walked me down to his room, he told me it was Ian’s birthday today — August 10th — and that he was turning 28. The tour manager knocked on Anderson’s door and Ian answered. I walked in and realized he was taller than I thought. We sat down at a table and as soon as I settled in, pulled out my $10 cassette player and $3 microphone, readied my notes and made sure the batteries worked, I said, “Happy birthday, Ian,” thinking that would be a cool way to start and break the ice. What a f**king mistake. He kind of grimaced and shot me a look of displeasure and disdain, a facial expression I’d encounter many times before the afternoon was over. Well, that sucked, I thought to myself. Though he was upset over the comment, he looked much younger than 28. His face was long and thin, wrinkle-free, a goatee sprouting from his chin. His hair was kind of reddish brown and an earring in his left lobe completed the picture of Anderson as pirate. He wore long black boots, dark pants and a t-shirt. His legs were crossed and rested comfortably atop the hotel room coffee table. Before I could ask my first question, Ian asked me one: “Have you heard the new album?” Uh oh. “No, Ian, I haven’t. The label didn’t get me a copy.” And there it was again, that look, that f**king horrible glare meant to wither and intimidate anybody on the receiving end of it. “You haven’t heard the record? How can you talk about it then?” I am reduced to single, non-intelligible grunts. “Er, uhh, mmm,” I mumble, a troglodyte. As I try and find a mental cave into which I can safely retreat, Ian brings out the guns again. “Well, we’re not going to talk until you’ve heard the album,” which further reduces me to a non-speaking primate. You know that evolutionary chart where the gorilla-type creature is on the far left, that monkey beast walking on all fours? Well, I’m somewhere to the left of that. I haven’t even made it out of the ocean yet. Lost in the metamorphosis unfolding in my brain, all rational thought now gone, my reverie is interrupted when Ian says, “Here is a cassette. Go and listen to it and come back in an hour.” It is a demand and not a request. I am shrinking by the second and will soon disappear completely. I retreat to my hotel room, put on the tape and begin making notes. As I’m listening to the music — which leaves me cold except for the title song, which harkens back to classic Tull — I can’t really blame Anderson for his response. Who wants to sit there with some uninformed journalist who hasn’t even heard your new record and have a conversation with him? I can understand that. What I don’t appreciate is why he had to be so dismissive and condescending about it, but what I’ll soon learn is that’s just how he is. I scribble notes and return to his room. We sit back down and begin talking. I’ve only had an hour to digest the entire album so it’s difficult remembering details but Anderson is satisfied I’ve heard the music. We talk for about an hour and he is verbose and has a lot to say, but he is generally one unfriendly dude. There is an edge about him and you never feel quite at ease, never want to turn your back on him. I ask him, “Why don’t you make albums like Stand Up or Benefit anymore?” No, I don’t say that but I want to. He is rude and disrespectful and I don’t like it. When the last word is spoken, I make a hasty retreat. Sometime later I interview Tull guitarist Martin Barre, and it’s like night and day. He is engaging, funny, sympathetic and sincere. I tell him he is an amazing guitar player and he is almost embarrassed by the compliment. It’s impossible to understand how that dynamic worked for as long as it did, but it’s precisely because Barre is so easygoing that he was able to roll with the punches, so to speak. And there was a lot of $h1t. In 2017, Anderson reformed Tull after a long period of inactivity to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the release of This Was. Barre was not invited to participate. In fact, Ian would eventually fire every musician who ever played in Jethro Tull. It was almost as if the flute player wanted nothing to do with the band he helped create. If any of you read my previous Behind the Curtain story, you know I buy and sell guitar picks. Well, I wanted an Ian Anderson pick and so I wrote to him. This is how he responded: “Sorry — I have only my own new guitar picks — Martin – .73mm M — and I use the same one for quite a few months before throwing it away. In fact I have some that sit in a guitar for many years. I am not a fan of overvalued memorabilia changing hands on eBay and elsewhere. Always a problem when giving to charity etc. It just gets sold on to others willing to pay silly money, especially when authenticated by the artist. If I am willing to sell my 1836 Martin or my 1937 Martin 0-45 I will let you know. There will be a free pick in the headstock. “My old stuff goes in the trash bin or is burnt.” Ouch. All he had to say was he didn’t have any, but that wasn’t enough. When I interviewed Martin Barre, I asked him everything and how it affected the entire Tull legacy but the guitarist wouldn’t rise to the bait. I knew he wanted to say more but didn’t, though he did acknowledge that Ian had totally blackened the band’s remarkable career. Notwithstanding, I still love Jethro Tull. Anderson is one of the most gifted songwriters on the planet and even if the band hasn’t released a good album in like a thousand years, they still remain one of the most creative and enduring groups of all time. Just don’t tell Ian I said so.

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Dec 23, 2020 7:25:11 GMT

www.ultimate-guitar.com/Jethro Tull Frontman Reveals Wage From Low-Paying Job Before the Band, Names Favorite King Crimson Song"The worst thing was the toilets, of course," Ian Anderson says. Posted March 11, 2020 09:07 AMDuring an appearance on My Planet Rocks, Jethro Tull leader Ian Anderson talked about his musical influences, his early days, King Crimson, and more. Asked about the low-paid jobs he did before launching a musical career, Ian confirmed that he used to work as a cleaner at the Ritz Cinema in Luton back in 1967 when the band was launched, saying (transcribed by UG): "That is absolutely true - only for a week or two. I think I managed to clean the whole cinema, including the toilets, on a rotational basis, you know? "You couldn't do it all in one day - me with a giant sort of industrial hoover and mops and brushes and buckets and things, and so I didn't manage to get the whole thing done. "And the worst thing was the toilets, of course. The only thing I got out of it apart from five pounds a week [around $120 per week in 2020 money] was a cracked urinal. "And the urinal, I've asked if I could have it since it obviously had a crack in it, it wasn't gonna be used, and they said, 'Yeah, you can take that.' "So I took the urinal with me, and it gave me the idea that one day I should have this on stage so we could pretend to have a pee in front of the audience, which indeed, John Evans, our keyboard player, did. "It was a ritual part of the show. Of course, there was nothing in it, it was just bolted onto the Hammond organ." You were influenced by the Big Band era and jazz more than rock 'n' roll? "Well, definitely because it was the Big Band jazz that my father had a few examples of in 78 RPM records and I was allowed, I think at the age of seven or eight, to play these. "And when I heard the earliest days of rock 'n' roll, particularly the very first couple of things from Elvis Presley, I recognized something familiar, and it was the syncopation, it was that slightly loose kind of jazz-blues sort of thing that was very seductive." With yourself having a lot of jazz influences, would you say the music of Jethro Tull is more planned? Do you have a strategy all the way through? "Well, it might seem like it, but I'm very much 'flying by the seat of the pants' kind of guy. "I do make things up very quickly and suddenly on the spot, it doesn't mean that I don't self-edit or throw out the rubbish or sometimes keep the rubbish because I can't think of anything better. "Whatever it is, I'm not as planned and calculating as maybe some people might think, but having said that, there is a plan, there's usually a plan; there's plan A, a plan B, and a plan C, and sometimes being on Plan C before I've realized that plan A was actually the best one in the first place." Elsewhere in the conversation, Ian talked about King Crimson, singling out 1969's "21st Century Schizoid Man" as a personal favorite. He said about the track: "It sits very well next to The Nice because at that time at the Marquee Club, King Crimson also began to play that year in 1969 and released an album ['In the Court of the Crimson King'], which had that track on it. "But yeah, those were poignant times, and '21st Century Schizoid Man' was one of these things that erupted from the stage of the Marquee Club, and off the grooves of your vinyl LP in a way that it had an angry and impassioned outpouring lyrically, and in terms of guitar playing too. It was a great track and remains one to this day." link

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Dec 26, 2020 7:17:43 GMT

music-illuminati.com/interview-ian-anderson-2018/Interview: Ian Anderson 2018BY ADMIN ⋅ MAY 28, 2018 Ian Anderson is the frontman / singer / songwriter / flautist / acoustic guitarist / musical mastermind for Jethro Tull, which is celebrating its 50th year. Anderson is the only member who has been with the band since its beginnings. Next up was Jethro Tull’s classic album Aqualung, released in 1971 and regarded by many to be the band’s best. This included the signature tunes “Aqualung”, “Locomotive Breath”, and “Cross-Eyed Mary”. Jethro Tull followed with two concept albums, both of which reached No. 1 in the US charts: 1972’s Thick as a Brick, and 1973’s A Passion Play. They released many more albums, notable ones including the compilation Living in the Past (1972), War Child (1974), Minstrel in the Gallery (1975), Songs from the Wood (1977), and Crest of a Knave (1987) which somewhat controversially beat out Metallica for the Grammy Award for Best Hard Rock/Heavy Metal Performance. This interview was for a preview article for noozhawk.com for Jethro Tull’s concert at Vina Robles Amphitheatre in Paso Robles, CA on 6/3/18. It was done by phone on 5/1/18. Jeff Moehlis: What are some of memories you have of Jethro Tull’s first tour of America? Ian Anderson: Well, good and bad. I think the first show was either at the Fillmore East or maybe the Boston Tea Party. It was an important gig, the first thing we ever did, so it was pretty nerve-racking. There was no kind of warm-up of maybe playing in a few Midwestern towns in a pub or a club somewhere. It was straight into the deep end playing two of the most iconic venues in that period of time – the Boston Tea Party where Dan Law was the promoter, and Bill Graham, of course, at the Fillmore East. So these were pretty scary places. You were in at the deep end, straightaway you were going to be judged by a very savvy audience and by two of the biggest promoters that have ever been in the USA. I guess it went OK, otherwise we would’ve been on the next flight home. But there was a lot of hanging around. We didn’t really have a lot of work, so there were days when we were just sitting in some terrible, terrible hotel sharing rooms and waiting for our manager to tells us we had another gig somewhere. So it was 13 weeks of being away from the UK to play maybe three weeks worth of shows [laughs]. It was a toughie. I think actually on that tour we supported Led Zeppelin in a couple of places, and memorably we played in Seattle with a band we were warned not to go anywhere near, not to talk to them because they were very violent and aggressive and scary. Quite nervously we did our soundcheck and waiting to go on before the MC5. You know, there were pretty scary onstage, but a couple of months later we were playing again in the USA and some of the guys from the MC5 came to see us in Detroit and were real pussycats, really friendly. They remembered us, and we were getting a bit more well-known and playing in bigger venues, and they came backstage to say “Hi”. And I met people like Mountain – Leslie West and Felix Pappalardi from the band Mountain. They subsequently went on to tour with Jethro Tull a couple of times. You know, there were lots of opportunities, I suppose, to see some of the great bands, sometimes to work with them, sometimes just being in the same hotel [laughs]. It was memorable, but as I say, good memories and bad memories. JM: The tour eventually found its way to California. What were your initial impressions of California when you came? IA: Generally speaking – I suppose it’s partly geographical – there’s an easier affinity between us Brits and, perhaps, New England. It’s partly geographic, but it’s also, I guess, because of a bigger concentration of immigration from England, Scotland, and Ireland, into what became the New England states and Nova Scotia, and even down the Eastern Seaboard, too. So that’s always seemed an easier fit. Once we got to the West Coast, everyone said, “You’ll love California. You’ll love San Francisco. You’ll love Los Angeles.” I suppose because it was talked up as being so great – fabulous weather, everything’s kind of laid back, and a lot of fun and palm trees and stuff – but I’m afraid I didn’t really take to it at all. I just hid in my hotel room for the first few years when I was in California [laughs]. I mean, of course we made the odd excursion out to Fisherman’s Wharf out in San Francisco, or to some club – I think the Whisky – in L.A. We sort of had a little bit of a look at things. We sort of sniffed the air. But I never felt very comfortable, particularly in Los Angeles. There were other parts of California I was more charmed by. I quite liked San Diego. I quite liked San Francisco, except for the experience of playing there in the early days, because it was the end of the hippie era and everybody was just out of their brains on whatever it was they were smoking or taking. I felt really outside all of that. I didn’t enjoy playing at the Fillmore West, for example. I really hated that. It was a very uncomfortable experience. I just felt like I was from Mars, you know, having nothing in common with the people in the audience who were there for a different kind of a celebration. Whereas playing at the Fillmore East was a little easier because it was a New York crowd, and they seemed a bit more awake and a bit more alert, and a bit more intent on listening to and judging the music. So I always found the West Coast to be difficult. But later on, it sort of changed around a bit. These days I don’t even stay in New York. If we have a show in New York we stay out of town, drive in for soundcheck, play the show, drive out of town as soon as we leave the theater, and stay somewhere 30, 40, 50 miles away in order to get away from New York. I feel claustrophobic and trapped in New York City, whereas I’m much more at ease now in California than I was. There’s little more sense of space. I still wouldn’t like to be stuck on any of the major freeways around Los Angeles at rush hour [laughs]. But it’s kind of easier. Your perspective changes a little bit as you repeatedly go to places. Several places I used to like I don’t like anymore, and some places that I really felt uncomfortable in now I quite enjoy going there. It just changes around. JM: I have a music question for you next. What inspired you to incorporate the flute into the music of Jethro Tull? IA: Well, desperation, really. I was a not very good guitar player when I was in my teens, and when I was about 18 years old I heard Eric Clapton for the first time, when he joined John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers. I realized that this guy was so far ahead of the pack, there was no point in trying to catch up. I was never going to be that good. Of course, then I heard about Jimmy Page and Jeff Beck and Ritchie Blackmore and other hotshots down in London who were doing sessions. It seemed the world was getting pretty crowded with very innovative and exciting guitar players. And then, of course, along came Jimi Hendrix, too, to make it impossible. So I looked around for something else to play. I suppose for reasons of practicality I had a harmonica, and learned to play a blues harmonica. And I bought a flute. I traded in my Fender Stratocaster for a cheap student-model flute and a Shure Unidyne III microphone, and armed with these two new things set off the South of England to try and give at least a year to be a professional musician. I didn’t do anything with the flute for the first few months, until around December of ’67, because we were approaching Christmas. I got the flute out and managed to get a few notes out of it, and then a few more. By the end of January, when Jethro Tull became Jethro Tull, I was playing the flute in quite a few pieces of music during the show. And then improvising. I tried to translate what I did on the guitar into the flute. It was just a different technique, different instrument, and by the time we recorded our first album, which I think from memory was about July of ’68, I mean I’d only been playing for about 7 months. At the time Jethro Tull became noticed, and there was a bit of a buzz about the band, I’d only been playing the flute, I suppose, for about 2 or 3 months. I made my name and reputation as a flute player really under totally false pretenses, because I never had a lesson in my life, and I really knew nothing about the flute, including for sure where to put my fingers on the keys or anything about it at all. It was just being self-taught, and fumbling around to try to find some things to do with it. There weren’t a lot of flute players around in those days. It wasn’t unheard of in pop music or in jazz or in folk music, of course. But it certainly wasn’t featured in any blues bands who were playing around at the time. I was the only flute player in terms of rock music until rock music developed, particularly in ’69, when the term “progressive rock” was first coined by the British music press. I had it pretty much to myself. There was a flute player in the Moody Blues, and Chris Wood in Traffic played flute a bit onstage. He was a saxophone player, really. And somebody in King Crimson, I think, also played a flute. And then, of course, along came Genesis, and Peter Gabriel played a flute, although I think wisely he decided not to continue with that. So for all of that period of time during the late ’60’s and early ’70’s I wasn’t having a lot of competition out there. So it seemed like a very wise choice to get away from the guitar and take up an instrument that was not very common in that musical genre. JM: One of my favorite Jethro Tull albums is Benefit, which I think has been overshadowed by the one that came next. Incidentally, Benefit came out in the U.S. exactly 48 years ago today. When you look back at that particular album, what are your reflections on it and its role in the evolution of the Jethro Tull sound? IA: There have been lots of albums that, I think, in their different periods have kind of set the bar for a change of genre in a different peak in the band’s career. Most notably, I suppose for me personally, probably the second album Stand Up is the one that marks the departure from the imitative kind of simple blues thing that we began with to finding more influences, more eclectic musical settings for simple songs that I was writing. By the time we got to Aqualung, another album that certainly made a big change for the band’s fortunes… It wasn’t instantly a huge hit out of the box, but it progressively sold over the next couple of years, particularly, but then to this day I suppose it is the biggest selling Jethro Tull album. And Thick as a Brick, which followed it, was the scary one, because after Aqualung what do you do? It seemed necessary to try something a bit braver, and Thick as a Brick was not something that I think our record company or our management were very comfortable with. They thought this was maybe a step to far, but I thought let’s push the boundaries a bit, and see if we can drag our fans down that rather more elaborate direction. And by putting it in a slightly comedic context, a slightly surreal humor environment, that I think was the wise and forgiving way of embarking upon that music. It was serious, but yet it was lighthearted and a bit of fun. So hopefully I wouldn’t be accused of being too deadpan, because bands like Yes and the early Genesis were incredibly serious. There was no humor attached to any of that, all of it was sort of showing off them being terribly serious about their music, whereas we were just having fun with the idea. We weren’t such good musicians as them, but we could put it in a more theatrical setting and have a little fun with putting an album and then a tour together which was not something that everybody else was doing at that point. I think maybe Alice Cooper had just begun, and that was the only other really theatrical act around at the time. That was a good thing to be part of, the feeling, particularly in live performance, that you were bringing elements in to make it more of a show, more of an experience that involved other elements, not just standing onstage playing your music. JM: Speaking of bringing humor into the music, I read that you were a big fan of Monty Python, and that Jethro Tull even helped to finance the Holy Grail movie. Could you tell us more about your Monty Python connection, and how they influenced what you were doing? IA: I think Monty Python were what you might argue were the third generation of British humor. They were the TV generation. Prior to that there’d been the radio generation of British humor, which really was the surreal humor that came out of a number of precursors. Some of the guys from Monty Python were into radio before they managed to get onto TV. It has a tradition, you see, that kind of slightly weird, surreal humor. It’s something very British, and goes back into some elements of humor that began even to the ’20’s and 30’s in music, and transferred into that kind of slightly wacky, weird radio stuff through programs like The Goon Show and Round the Horne, and other radio things of the ’50’s and ’60’s. And then Python came along, and of course after they’d had their run at it essentially in the early ’70’s, it evolved into other British humor, into a number of rather surreal and weird camp kind of performances from different musical troupes, who in the tradition of Monty Python took TV by storm, at least for a while. So it’s something very British. It’s something that I think influenced us – when I say us, I mean we British musicians, not just me or Jethro Tull. It was something that I think we all kind of tuned into. We felt it was ours. We felt it was a very national form of humor. We felt it was British. Of course, it was making fun of the British most of the time, but we’re good at making fun of ourselves. So we all rather liked that. When Monty Python were making their Holy Grail movie, and the word was no one would fund them, no one would put up they money, we in music industry – a few bands including members of Pink Floyd, Led Zeppelin, and me, and the managers, and folks who were involved in some of the record companies back then – we put up money to fund making the movie. To this day, I get a royalty check, which is nice to have from something that you were a part of getting it to happen. My only regret is that Life of Brian, which was I think a bigger, more important movie than Holy Grail, we didn’t get the opportunity to invest in, because somebody told a little fib to Pythons and put up all the money, and we were excluded from the funding of Life of Brian. Traditionally in the theater, the term “angel” is the one that’s used for coming to the rescue and putting up the money for a production, and if that production is successful then traditionally you get offered the follow-up. You know, you become an investor is somebody’s life and career and commercial and artistic success, and you’re invited to participate again if it’s successful. And unfortunately we were not able to do that, so I, for one, was a bit pissed off about it. But I know for a fact that the Pythons were told a fib, because I spoke to John Cleese about it some years later and he was quite surprised that he’d been told that none of the original investors wanted to participate again. When I asked him who told him, then it became clear that a bit of subterfuge had gone on. JM: You’re being very coy – I assume you don’t want to name who told the fib? IA: Well, if he was alive today then I certainly would mention his name, because I feel angry about it. But I think we’ll leave the dead to their own memories that we prefer to have about them. JM: Fair enough. As something that I perceive as humor in the music of Jethro Tull, on Passion Play there is “The Story of the Hare Who Lost His Spectacles”. I have a friend who calls that “Winnie-the-Pooh on acid”. What inspired that story, and that music? IA: That, I have to say, was largely to do with Jeffrey Hammond. I just wanted some surreal moment… There were two sides, because we’re talking about vinyl records back then, and I wanted something that would be the end of Part 1 and the beginning of Part 2, something a little different that would separate the music in a way that gave this little hiatus between the two sides, that it would have its own rather curious and surreal identity. So Jeffrey came up with “The Story of the Hare Who Lost His Spectacles”, wrote the words, and the idea was it would be a spoken word piece and John Evans and I came up with some musical ideas and we put that together. It was Jeffrey’s baby, really. He was the one who came up with not only the words, but actually performed it, and of course when we then came to make a video that we used onstage when we did the Passion Play tours, Jeffrey was very much at the center of that as a performer. You know, Jeffrey was one of those guys who if you met him in private life he was incredibly shy, really the antithesis of a performer. He liked to really just have a quiet life away from the glamor and the pizazz. He was embarrassed to talk to fans or strangers. I mean, he was not exactly a recluse, but just a very shy and private person. But when he walked onto the stage, he became ten times larger than life. And that was always the very exciting thing about having a guy like that in the band, who went through this metamorphosis every night [laughs]. Five minutes before he walked on he became this completely different person for the next couple of hours, which was great. Jeffrey came to one of the shows three or four weeks ago, when we started the UK tour. He had been quite ill for the last few years. It was great to see him out of the house. He looked pretty well. I think he enjoyed the rare occasion of going out of his house and doing something, and being with other people. So I think he probably found it exhilarating, but exhausting, too. He tires quickly. But it was good to see him, and he was in good form. He contributed a little bit to the show in ways that people will see when they come to the show. JM: I interviewed to you about two years ago, and we were talking about similarities between songs, like [Jethro Tull’s] “We Used to Know” and “Hotel California”. I mentioned to you a song by Country Joe and The Fish called “Love Machine”, which reminds me a bit of “Locomotive Breath”. Did you ever get a chance to listen to that? IA: I think I did, because I remember you telling me about it, but I don’t recall what my conclusion was. It’s, of course, the case that people, without being directly plagiaristic… You know, you hear stuff on the radio and you’re aware of other things going on in your musical world, and you kind of half-remember little things. They all sit there somewhere in your head. When The Eagles were on tour with Jethro Tull, actually as an opening act back in the early part of 1972, we were still at that point playing some of the music from previous albums, including the song “We Used to Know”. I guess The Eagles probably heard us playing it onstage. They may well have heard it on the radio, anyway. But I’ve never accused The Eagles of plagiarism. You know, I can see the similarities, particularly in terms of the chord sequence, the actual harmonic nature of it. But the time signature is completely different, the melody is substantially different, and the lyrics, of course, are totally different. So, for my money, The Eagles came out with one of the best and most classic pop-rock songs ever. I mean, who would not liked to have written “Hotel California”? If there’s a little bit of my song kind of in there, then I am flattered. I’m certainly not someone who would accuse them of plagiarism. I never have. Other people have continued to make that comparison to this day. JM: My last question for you is kind of obscure. There’s a song called “Left Right” which was finally released on the Nightcap album. To my knowledge it was never recorded again, although pieces of it perhaps figured into “Baker St. Muse”. What’s the story behind that song? IA: Well, it’s just one of those pieces. There’s lots of them over the years, particularly in the ’70’s – you know, outtakes, things that were tried, demos that were made and half-recorded in the studio. You know, a few of those were found for the Songs From the Wood album and for the 40th anniversary remix that Steven Wilson did of Heavy Horses earlier this year. So some of this stuff does find its way out there eventually, and in various states of repair, because quite often they were unfinished studio recordings. They’re of interest, I suppose, to the fans who just simply want to hear everything, but I’m pretty guarded about it because somewhere along the line I had taken the decision as a record producer not to go further with that idea. So, whatever my reasons were at the time, it was something that you could consider as not being up to the standard, or certainly not fitting for a particular album. So I’m a little wary of going back and saying, “Oh well, we’ll release that anyway.” It’s just something I’m told some of the fans at least are really interested in. But I have a bit of a reticence about doing this, and certainly there are things that have been put in front of me, old tapes that have been discovered, and I’ve said, “Listen, I’m sorry, but that absolutely is not something that I want people to hear.” Sometimes it’s because it’s a crap song, but it could also be because maybe somebody’s performance is really not up to the mark, and I would be embarrassed for them if that was made public. Bearing in mind, we’re talking about things quite often that are just demos, just fooling around it a preparatory state in the studio. I don’t think it’d be very fair to some people if they got to hear somebody trying out some ideas in an arrangement that didn’t work.

|

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Jan 1, 2021 18:14:41 GMT

What would a world without Beethoven be like?  Deutsche Welle (DW) is celebrating Ludwig van Beethoven's 250th birthday! Deutsche Welle (DW) is celebrating Ludwig van Beethoven's 250th birthday!

In the two-part series “A World Without Beethoven?”,

Sarah Willis – French horn player of the Berlin Philharmonic – asks famous

musicians to ponder what the world would be like had Beethoven never existed.

Sarah Willis talks with film music composer John Williams (“Stars Wars”, “Jaws”,

“Harry Potter”, “E.T.” etc.), and asks legendary jazz trumpeter Wynton Marsalis to

explain the syncopated challenges of jazz. Singer-songwriter, arranger and record

producer Van Dyke Parks (Beach Boys/“Smile”) tells her about pop’s concept albums,

and rockers Ian Anderson (Jethro Tull) and Rudolf Schenker (Scorpions) agree that

the famous "da-da-da-dum" of Symphony No. 5 is the mother of all rock riffs.

The various musicians’ answers confirm: Beethoven's innovations continue to

influence music up to this day – extending far beyond the classical genres.

|

|