|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Sept 1, 2017 12:10:43 GMT

themusicsite.com/music-news/interviews/interview-ian-anderson-jethro-tull-officialjethrotullInterview: Ian Anderson of Jethro Tull Posted by Dana Miller | Aug 31, 2017 | 2018 is a bit of time out to be musically reflective on stage as we focus on the

origins of Jethro Tull and 2019 will be a return to the next chapter of events with

a new studio album. We have recorded some new material for a studio album

but it won’t be completed for a while and is not scheduled until 2019.

life is not a certainty for anyone and 2019 seems like 100 years from now !!!

Maybe he was misquoted ?

|

|

|

|

Post by steelmonkey on Sept 1, 2017 16:56:51 GMT

2019? Waaaaaah...I thought the new stuff was next Spring...or summer at the latest. Jesus Christ and John Lennon, why so long to wait?

|

|

|

|

Post by tullabye on Sept 2, 2017 2:10:46 GMT

2019? Waaaaaah...I thought the new stuff was next Spring...or summer at the latest. Jesus Christ and John Lennon, why so long to wait? Every quote I've seen refers to next spring around April, so more than likely just a misprint. |

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Sept 2, 2017 7:50:19 GMT

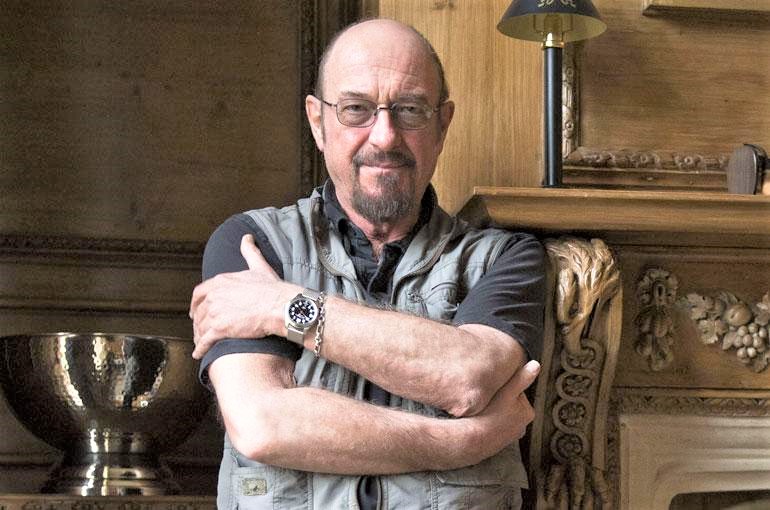

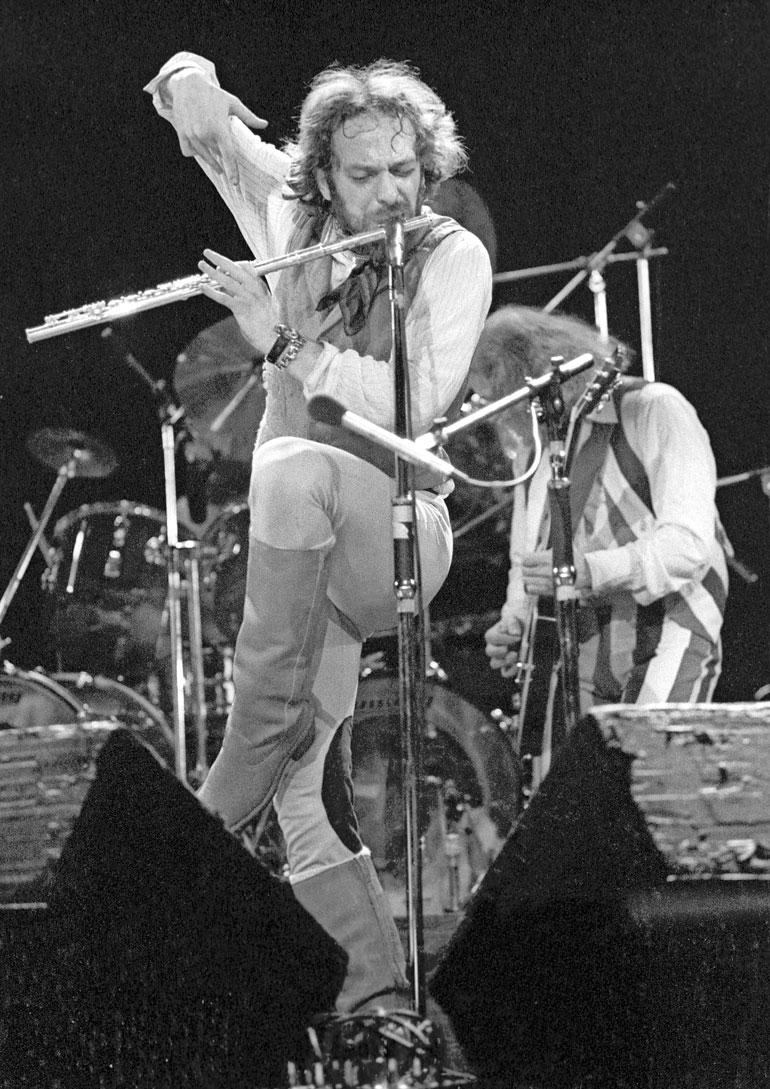

2019? Waaaaaah...I thought the new stuff was next Spring...or summer at the latest. Jesus Christ and John Lennon, why so long to wait? Every quote I've seen refers to next spring around April, so more than likely just a misprint. By PAUL DAVIES PUBLISHED: 17:57, Fri, Sep 1, 2017  Jethro Tull are one of the biggest selling rock bands of all time Jethro Tull are one of the biggest selling rock bands of all timeJethro Tull are one of the biggest selling rock bands of all time. Their immense and diverse catalogue of work encompasses folk, blues, classical, progressive and heavy rock. The group became one of the most successful and enduring bands of their era, selling over 60 million albums worldwide. Founder, frontman, songwriter and flautist Ian Anderson is rightly credited with introducing the flute to rock as a front line instrument, not to mention the codpiece in his famous theatrical live performances. Their debut album This Was was released in 1968. Now, with the 50th anniversary approaching, to celebrate this Golden anniversary Ian Anderson will present 50 years of Jethro Tull in eight UK concerts during April 2018. Express.co.uk catches up with a busy Ian Anderson as he prepares for the forthcoming activities surrounding his band's milestone. Jethro Tull played their first concert at the famous Marquee Club in 1968 of which Ian has fond memories. Ian recalls: " It was actually the fourth time that we played there as a band, albeit under other names in the weeks before. We knew the venue and its manager. It was important to do well there and build a following as a stepping stone to venues in other cities." As the frontman of a rock band, Ian attracted a lot of attention by playing the flute when not singing, thereby creating the defining sound of Jethro Tull. Ian explains: " It was Eric Clapton that inspired me to take up the flute, in a roundabout way. I was a guitar player in 1967, but I soon realised that I would never be as good as Clapton. So I looked around for another instrument, one that he and the many other great guitarists of the time couldn't play. It's better to be a big fish in a small pool than the other way round." With worldwide sales surpassing 60 million albums, Tull mastered and covered a wide range of musical styles from folk, classical and progressive rock - Anderson was named Prog Rock God by the highly acclaimed Prog Magazine in 2013, this years recipient is the equally legendary Carl Palmer of ELP - Ian finds combining all musical forms quite a test to play in a concert. He says: " They are all a challenge to play in their different ways: technically, musically and emotionally. My favourite songs to play on tour are pretty much the same as the fans. There are some 300 songs to choose from in theory, but maybe about 100 in practice. My own favourites come and go and I keep re-discovering material from the earlier albums which capture my attention and my heart. At least for a while." As the sole songwriter for the band, Anderson clearly has a lot on his very full plate when it comes to writing an album and shaping its direction. He doesn't wait for inspiration to strike, but adopts a hard work ethic to his approach. He reveals: "I find it quite easy to write music today. The lyrics are the most demanding, so I have to learned to tackle the words early on and not leave them to later. I'm not really a believer in inspiration. I adopt the notion that you have to go looking for it rather than wait to be visited by the muse. After a fruitless hour or two, something usually comes along. As I get older, the process has speeded up a bit. I assumed that it would get harder but have found the reverse to be the case. I definitely find it easier to write songs these days, but not necessarily easier to write good ones!" With the 50th anniversary concerts in mind, the band will be playing material from all eras and genres. There have been many talented musicians who have played their part in Jethro Tull over the past fifty years. Will any of them be joining Ian on the tour? Ian reflects: "There have been over thirty two band members in the band, so it's a little impractical to factor in some without leaving out others. The four guys with me for the last twelve years have their marbles, their own instruments and their boarding passes. Many of the past members gave up music a long time ago or are not able to play anymore. A few, sadly, are no longer with us..." Clearly with an ongoing career lasting fifty years, Anderson has plenty of recollections and stories from the road to fill an auto-biography if he so chooses. Especially, coming from a band that has topped the charts and headlined all the famous concert halls around the globe. Ian shares some of those stories that can be printed with express.co.uk. Ian says: " There are so many stories that I can't share. Or, rather, shouldn't share! I once had a violinist travelling with the band and crew on the tour bus. I asked her to share with me her experiences of being the only girl on the tour. She replied, 'what happens on the tour bus, stays on the tour bus'. I thought it best to leave it at that...but memories of things happening to me, whether funny or downright embarrassing, have never been a problem to talk about. Being struck on my bare chest by a used tampon during a show or having a pint of pee poured over me as I walked out to the stage in Shea Stadium come to mind. Rather brings a man down to earth, wouldn't you say?" Such lurid experiences happen very rarely now to a band entering its half century. And with the creative juices flowing Anderson is still not one to dilly-dally. There is plenty of activity planned involving special re-releases of albums and newly recorded material in the making too. The legendary frontman adds: " I have actually postponed the new studio album until early 2019 to avoid the plethora of re-releases, boxed sets and live stuff coming out in 2018. I think that next year, uncharacteristically for me, should be a year of looking back and celebrating past times, rather than unleashing unfamiliar new material on a nostalgic fan base."Any new Ian Anderson Jethro Tull release will ensure that this venerable artist and band will continue towards its Diamond celebration. Ian teases: " We have already recorded half of the songs for the next studio album which I wrote last January. It is frustrating to leave it for a while, but probably best to. I just have to hope that no one else comes up with the same title or concept during the next 18 months. Otherwise, back to the drawing board!" |

|

|

|

Post by samatcn on Sept 3, 2017 11:59:34 GMT

Well, 2019 doesn't seem that close at all, in comparison to april 2018. I think postponing the album might be a mistake, but I guess we'll have some stuff to fill the gap. I'm thinking the rock opera live album might be getting a release date in 2018 then, as it jives somewhat with the "looking back" theme, and hasn't had a preliminary release date discussed from what I've seen. Man I really wanted that new album!

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Sept 13, 2017 14:08:13 GMT

The Popdose Interview: Ian Anderson Is Not Living In The PastSEPTEMBER 13, 2017 To Ian Anderson’s mind, at this stage in a career that will span fifty years come 2018, “Jethro Tull” is less a fixed institution than an idea that has encompassed the talents of “thirty-three different people who have passed through the ranks of the band.” Among these figures are the band members who currently work with him, from the previously Jethro Tull-credited tour to this year’s exploration of the catalog: Florian Opahle, electric guitar; John O’Hara, piano, organ, keyboards, accordion; David Goodier, bass guitar; Scott Hammond, drums, percussion; and Ryan O’Donnell, providing additional vocals.popdose.com/the-popdose-interview-ian-anderson-is-not-just-living-in-the-past/

|

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Sept 14, 2017 1:43:16 GMT

The Popdose Interview: Ian Anderson Is Not Living In The PastSEPTEMBER 13, 2017 To Ian Anderson’s mind, at this stage in a career that will span fifty years come 2018, “Jethro Tull” is less a fixed institution than an idea that has encompassed the talents of “thirty-three different people who have passed through the ranks of the band.” Among these figures are the band members who currently work with him, from the previously Jethro Tull-credited tour to this year’s exploration of the catalog: Florian Opahle, electric guitar; John O’Hara, piano, organ, keyboards, accordion; David Goodier, bass guitar; Scott Hammond, drums, percussion; and Ryan O’Donnell, providing additional vocals.popdose.com/the-popdose-interview-ian-anderson-is-not-just-living-in-the-past/

and still having an audience waiting to see what comes next. It was very gratifying when our tickets went

on sale last week for some dates in the U.K. in May next year, and we immediately sold 70% of the

Albert Hall.It’s very encouraging to know that you have a group of dedicated fans who are rushing out there

to buy tickets for a concert that’s some ten months away.

This is one cool interview. Thanks Graham for posting this.  Almost 50 years since TULL was born. Almost 50 years since TULL was born.  |

|

|

|

Post by steelmonkey on Sept 14, 2017 16:52:25 GMT

The attrition rate in the next 10 months need to be factored into actual attendance...will there be enough of a demand for tickets that night being sold in front of the venue by the friends and families of those of us who expire before the gig?

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Sept 16, 2017 7:27:56 GMT

www.thatericalper.com/2014/09/14/best-touring-advice-ever-from-jethro-tulls-ian-anderson/Best Touring Advice Ever From Jethro Tull’s Ian AndersonSep 14, 2014Since the last time we talked, are you still managing your own tours?I don’t have a tour manager because I don’t want to have another guy who will spend my money and do things differently to me. I know exactly where I want to stay. I know exactly which airline and what time I’m going to fly, and what aircraft I’m not prepared to fly and, in a few cases, which airline I’m not supposed to get into for fear of dying. There comes a point where you really don’t want to let somebody else mess things up when they’re going perfectly fine the way they are. Happily, let’s say in the last 15 years, the Internet has provided me with the opportunity to do the research of a tour, anywhere in the world. I can find how I’m going to get there, where I’m going to stay, what I’m going to do – every aspect of the whole thing can be ascertained by internet access. And while you’re there, you might as well press the button that says “buy flight” or “pay for hotel now.” There’s little point in doing all of this if you then give it to somebody else. It will take you twice the time and cost you a whole lot of money. And there’s always a chance that somebody screws it up. I’m perfectly happy being a Sunday afternoon travel agent. That’s one of my hobbies. On Sunday afternoons, if I’m not on the road, I sit and book flights and hotels and travel arrangements, and do tour itineraries. I find it a lot of fun. It’s a hobby. You mentioned in our last interview that you were giving Mike Rutherford advice about making touring profitable. Can you elaborate some more as to how you know touring strategies rather than a tour manager – allegedly the person who knows all this good stuff?Well, a tour manager isn’t going to do tour budgets and have the experience or the ability to deal with all the aspects of withholding tax and issues that are perhaps way beyond his remit. A tour manager is essentially a shepherd with an unruly flock. A tour manager is a guy who probably has some experience of travel more than anything else, but his role is fundamentally to be traveling with the band and escorting them through airports and train stations and on and off buses. But I don’t work with sheep. I work with musicians. My experience has always been that if you give people the responsibility of behaving like professional musicians, they will rise to the occasion. If you treat them like sheep, they very quickly become sheep. Having a shepherd is not an ingredient that is part of my way of doing things. … You have to imagine the majority of people in rock bands probably do sit down once in a while and say, “I’m going to take my family to, oh, the Carribbean,” and they’ve got to go online and check out some hotels, flight options, whatever, or maybe they’re so incredibly inept and boring that they call their travel agent and say, “I want to go somewhere nice! Send me some tickets!” I’m guessing but I think most people are capable of booking their own holiday for themselves and their family. And that’s the way I look at it when I’m booking tours. It’s me. It’s my friends and family. It’s my musical family and I’m looking out for them, making sure they get safely from A to B, that they all have access to their flight booking reference numbers, and they can check in online, choose their seats and so on, all of which they’re very capable of doing. And I see them on the plane! I don’t have to escort them through an airport. They’re grown up lads; they know what to do. So what can other tours do to help their budgets? The economy of scale is everything. If you end up with four guys in the band and 20 crew, you’re probably doing something wrong. I mean, there may be an artistic reason for doing that but it’s most likely that you’re way, way overemploying people. And, of course, people will make themselves indispensable … and therefore make [musicians] dependent on them. That’s what I mean when I say if you treat musicians like sheep they become sheep. So yeah, I think you’re probably talking about a ratio of 1-to-1 depending on a few variables. But if you’re planning on a lot of production then you’ve probably got twice as many crew because you have lighting guys and sound guys and drivers and buses and trucks. But for an average rock band, think in terms of one truck and one bus. That’s probably all you really need, unless you’re Madonna or Lady Gaga. So you’ll find a bus is the most economic thing in the USA. It’s for sure the best way to do it as long as you don’t give everybody the luxury of hotels as well, except on days off. In my case, try to play five nights a week on average. Otherwise your days off will be very expensive. … You’ve got to make tours cost-effective, it’s economy of scale, do enough dates to make it worthwhile. It’s about sitting down and planning it in the first place. A simple spreadsheet gives you the answers. Someone comes up to me with an offer for a show, or two or 10, the first thing I do is a quick trial budget. Say we’re going to Australia. It’s only going to take me five minutes to check out the flights. It might take me a quick double check to see withholding taxes in that country, how I might offset it with expenses and so forth. Maybe 10 minutes to do a trial budget based on the information. Let’s say 20 minutes, half-hour tops I know whether that tour is worth pursuing. I can go back to my agent and say, “Frankly, it’s not quite worth it for me to do this.” Or, “Let’s go ahead with it. Maybe they can pay another 10 percent higher fee than what they’re offering. See what you can get.” Or I can say, “I think they’re paying us a little too much here and I think they’re taking too big a risk so why don’t we try and negotiate, give them a little headroom to try and make a profit and reduce the fee.” Which, on occasions, I might well do. But it all depends on that first, crucial decision to spend half an hour on that analysis. It’s not a huge chore. I like that I can do it fairly quickly. I can go into my standard insurance costs and administrative costs amortized across the year. All that stuff is built into the spreadsheet. I just hit the return key and see if there’s a meaningful profit at the end for me to put into my bank account before I pay my 50 percent tax that I do in the U.K.

|

|

|

|

Post by JTull 007 on Oct 8, 2017 2:49:37 GMT

Ian Anderson Interview by Tony Loconsole Vintage Sound 93.1 Fm

Jethro Tull has sold more than 60 million albums around the world and has performed

more than 2600 shows in over 40 countries. Now comes a new album by Ian Anderson

and the Carducci Quartet called 'The String Quartet', on sale now at Amazon.com & i-tunes.

The album showcases the classic songs of Jethro Tull, including "Aqualung", "Living in the Past",

& "Bungle in the Jungle", and features Ian playing flute on most of the tracks.

Ian says, “Perfect for lazy, long sunny afternoons, crisp winter nights, weddings and funerals.”

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Oct 12, 2017 7:40:23 GMT

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Oct 25, 2017 7:58:51 GMT

www.poprockbands.com/jethro-tull/item-news/prj-da20171018-C1361F0774.htmlDear Jethro: A heart-to-heart with British rock legend Ian Anderson Jethro Tull's Ian Anderson talks mortality, the rock hall and more before Nov. 9 show at the Mahaffey. BILL DEYOUNG OCT 18, 2017 10 AM  “Generally speaking," Ian Anderson says, "musicians get to go on past their sell-by date. Actors, too. “Generally speaking," Ian Anderson says, "musicians get to go on past their sell-by date. Actors, too.

They have that tendency to go on almost to the point where they pop off."

LEIGHTON MEDIAThese days, Ian Anderson is all about blurring the past, the present and the future. “Believe it or not,” he says, “there are still many people who think Jethro Tull is the man who stands there playing the flute on one leg.” There is no one called Jethro Tull. It is – well, it was – the name of a very, very popular English rock band. Some 60 million albums sold globally - benchmarks like Aqualung, Songs From the Wood, Thick as a Brick and Minstrel in the Gallery. Ian Anderson wrote and sang every song, produced every record, dotted every “i” and crossed every “t,” for well over 40 years. And yeah, he still plays the flute standing on one leg. Still, “Even to this day I get letters addressed to ‘Dear Jethro.’ I get people coming up to me in the street saying ‘Oh, Jethro – I named my second son after you.’” For all that time, Anderson was quite content to issue his complex, idiosyncratic and delightfully melodic music under the collective name of Jethro Tull, regardless of which auxiliary musicians happened to be on board at the time (there were more than 30, all told, over the years). He’s just turned 70, and that’s why he now performs as “Jethro Tull by Ian Anderson” (he’ll be at the Mahaffey Theater in St. Pete on Thursday, Nov. 9). Even though the four guys in his current band were, at one stretch, actual members of late-period Jethro Tull. Confused? Anderson understands that. “Before I pop off, I just have this feeling that I want people to know my name,” he says with a chuckle. “That I’m the continuity factor. There’s so many bands around where the principal performer is no longer part of it. There’s a fairly endless list of those sorts of things.” He cites the Doors, Queen and Creedence Clearwater Revival as the most obvious examples of “classic” outfits that tour without their chief singer and songwriter. “With a band of our vintage, I guess there’s a tendency to think ‘Well, it’s a glorified tribute band.’ So with my name there, I hope it gives it that authenticity. Being the songwriter, the guy who stands in the middle and waves the flute around. And the producer. And, since 1974, the manager of the band.” Along the way, Anderson made the odd “solo” record, including the lush and exotic The Secret Language of Birds, the complex Homo Erraticus and, most recently, Jethro Tull – The String Quartets, which reached No. 1 on the classical charts. The dry and often wickedly dark humor that runs through Anderson’s work is a large part of its charm. It was an uninterrupted vein that unified Tull’s “prog” period – Thick as a Brick and A Passion Play – its “English folk” period – Songs From the Wood, Heavy Horses and Stormwatch – and its heavy rock, blues and light acoustic numbers. Always coupled, of course, with exemplary musicianship and exciting, electrified live shows. He’s got that typical English way of looking at his own mortality with a nod and a wink. “I’ve been thinking about that since 1975, when I wrote the song ‘Too Old to Rock ‘n’ Roll, Too Young to Die,’” he explains. “Generally speaking, musicians get to go on past their sell-by date. Actors, too. They have that tendency to go on almost to the point where they pop off. There’ve been a number of actors who’ve died during the making of their final movie, leaving someone else to come in and finish the job." “That’s the sort of ending I suppose one would like to have. It’s a bit of a John Wayne cowboy movie kind of ending. The cowboy dies with his boots on. And that’s the way, I suppose, that most of us would like to go.” Is he imagining an onstage death, one last ‘Locomotive Breath’ flute solo and down he goes? “I’d prefer to get to the last three or four bars, rather than the middle,” Anderson laughs. “Or maybe even getting as far as my dressing room after the show! As long as there’s a cold beer waiting for me.” There’s one other thing to talk about. Jethro Tull have been eligible for induction into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame since 1993. And still, nothing. That this important, influential and beloved band isn’t in the Hall is one of its most (of many) egregious omissions. Anderson’s long-held position – he gets asked about it a lot – is that he doesn’t care. In lieu of discussing it further, he tells a story. When the actual Hall opened in Cleveland in the 1980s, he was among the first to donate stage costumes and other ephemera from his storied career. “I remember walking past the display cabinet and seeing Rod Stewart and me – well, sort of dummies wearing our clothes – and thinking ‘Aren’t we tiny? Aren’t we really, really, really tiny little men?’ “I thought, the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame needs to find a new Chinese laundry, or a dry cleaner, because they’ve managed to shrink these things to the point where they’re too impossibly small for anything vaguely humanoid to have ever worn onstage. I think Rod Stewart and I are about the same height. “A couple of Brits behind the safety of a glass cabinet. That’s not a bad place to be. That’s enough for me! This who idea of being inducted absolutely doesn’t register on my radar as being good bad or whatever.” Jethro Tull by Ian Anderson Thurs. Nov. 9, 8 p.m. Mahaffey Theater, 400 1st Street S., St. Petersburg, $49.50-$124.50 More info: local.cltampa.com

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Oct 26, 2017 7:40:18 GMT

www.theaquarian.com/2017/10/25/ian-anderson-jethro-tulls-early-beginnings-and-new-starts/Ian Anderson: Jethro Tull’s Early Beginnings And New Starts—by Mike Greenblatt, October 25, 2017 There was hardly any rock ‘n’ roll on Jethro Tull’s 1968, This Was, debut. Filled as it was with jazz and blues led by eccentric and multi-faceted, Ian Anderson, who would hop on one leg and spew out the Bach as readily as the rock. Forty albums later, the most recent of which is The String Quartets, arranged by current Jethro Tull pianist/accordionist, John O’Hara, with The Carducci String Quartet, Anderson is taking his merry men out again. The show is a multi-media greatest hits assemblage bound to please any Tull fanatic, as well as your mom. We caught up with the notoriously opinioned curmudgeon just prior to leaving for Brazil where the tour starts. Ian, you see, prefers audiences outside the U.S. But, we’ll let the man tell it to you himself. The addition of vocalist Ryan O’Donnell on the Thick As A Brick 2 tour was a stroke of genius. What led you to that decision?Two reasons. One was that on the original Thick As A Brick recording, there was quite a lot of places where flute and vocals occurred at the same time. If I was going to try to recreate as much of the original album as I could, something would have to go, but to bring in another flute player would’ve been very weird, so I brought in a singer. I couldn’t just give Ryan a few lines in the course of a two-hour show, and because of his experience in musicals as a singer/actor, he brought a more theatrical flair to the presentation. It also gave me the freedom to play more flute, yet still have time to draw a breath before having to sing again. It was a pragmatic decision. Ryan also appeared a couple of years later on my Homo Erraticus tours. He then joined the cast of The Kinks musical in London’s West End (Sunny Afternoon) as Ray Davies. It’s a very demanding and exhausting role and he’s been doing it every night to packed crowds for two years now. It’s a great show. I went to see it myself and loved it. Then another vocalist, Unnur Birna, from Iceland, joined the cast of your Rock Opera tour a year or so later, but only on the big screen behind the band. As was Ryan. She did the video shoots too. Both of them were my virtual guests for the next 18 months of shows. The three U.S. tours planned now will all be sung live, with those two relegated to short on-screen appearances. I’ll never forget when you had the delightful violinist Lucia Micarelli with you who went on to star in HBO’s Treme. You seem to have a very good ear for discovering new talent.If you think of the history of Jethro Tull over the years, there’s been over 30 members in and out of the band. They’re all folks who have their special abilities and talents. Just as you can credit John Mayall for having brought many musicians into the ranks of his Bluebreakers, who went on to enjoy successful careers like Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker, Jack Bruce, Mick Fleetwood and Mick Taylor. Just like a little earlier Alexis Korner had both Mick Jagger and Robert Plant in his blues bands. Nurturing young talent is a priority if you want to be a good band leader. Like Art Blakey & The Jazz Messengers, which was like a finishing school for generations of big jazz stars.Same for the bands of Frank Zappa and even Captain Beefheart, although in his case, his style pushed people away from the band rather than be the captain of a happy ship [chuckles to himself]. I’ve always thought it was nice to work with different people and when the time came to move on, it’s usually a mutual decision. Bassist, Dave Pegg, for instance, spent about nine years in Jethro Tull while still in Fairport Convention. I know you’re not going to be able to bring the Carducci String Quartet on the road with you but, damn, they do add a lot to your current Jethro Tull: The String Quartets album. You picked the right songs with having so many to choose from. What songs almost made the album but didn’t? Might there be a Volume 2?It really takes quite a long time to develop those arrangements. Some of the songs were an easy fit, yet some of the more rock-oriented songs had to be reconstructed. Each song on its own merits required a different approach. John O’Hara did a lot of work arranging. We went into a church to record a lot of it. Carducci has a pretty filled date sheet in many countries of the world playing classical festivals. The chances of getting them to go out with us are very slim. And it didn’t make any sense to say yes to the numerous offers we got to do a one-off show together because of the time it would take to rehearse. Here’s hoping they play some of these pieces on their own tours. But how great would it be to see them with you at Red Rocks, for instance, in Colorado. It’s on my bucket list to go to that beautiful venue one day.It’s very cold. Performing outdoors, a mile up in the clouds in the best of times is a very hard place to play. I practically need oxygen to play flute and sing. You struggle with very low humidity, freezing temperatures, and it is, really, quite difficult. Mexico City and La Paz (Bolivia) are like that too. You suddenly realize how your flute sounds very thin and reedy, losing its body and volume as if there’s something wrong with your instrument. That dry thin atmosphere robs you of the air you need to properly perform. I love the shock of recognition as each song on the new CD unfolds. I do not want to know what’s in store and when you open with “In The Past,” with that melody that’s imprinted upon my brain like a tattoo, it was like an electric shock.With some of the tracks, there was a deliberate attempt to reconfigure the song—like with a cello cadenza—by teasing people so they know not which song it is but are lured into it and then bam they know what it is. That’s ok to do two or three times but it would be a bit of a bore if done on every song. “Pass The Bottle,” for instance, was originally recorded in 1968 as, “A Christmas Song,” with a string quartet anyway. It was important for me to include that because it was the first time I ever worked with a string quartet. I remember seeing you at MusikFest in Bethlehem, Penn. and you got really upset that night and stormed off the stage in a fit of anger depriving us of “Aqualung.”I really don’t remember specifically what the problem was, but it was most likely something that annoyed me in terms of the audience whistling, shouting, hooting and generally making so much noise that it became impossible to concentrate on the music. Unfortunately, that’s the way people are. I attended one of the final concerts of Black Sabbath recently in London. The reality is that they play very loudly despite (lead guitarist) Tony Iommi not really liking to do so. They do so just to overcome the inevitable crowd noise. They cover it all up with brute force volume. Jethro Tull has more dynamic variation and the crowd uses those quiet moments to screech out their whistles and such or shout out at you. You then have two choices: You either try to struggle on and blot it all out, or you get mad. You think I’m the only one? I know many artists who get truly pissed off at crowd interruptions, the flashing of cameras and cell phones, the utter lack of respect for the artist. It just seems to be that in certain places, folks seem to think that’s ok. Maybe I’m wrong and they’re right. I just don’t really want to get drawn into it but I know when I play outdoors in the U.S.A., especially in the summer, it’s going to be a rough ride. I find that fascinating.It’s not fascinating! It’s a pain in the f**king ass. But it’s what I do for a living so I have to put up with it. Forgive me once in a while if I lose my temper. Somebody inevitably will shout out something unpleasant at the wrong moment, I will lose my temper and shout back. Or I will walk off the stage. Most times, I try to blot it out. But trust me on this. It is a really rough ride for musicians. I’m not happy when people shout me down when I am totally trying to concentrate of what I am doing on stage. It makes it difficult. I don’t get that in other countries. I remember once at the Beacon Theatre in New York City, I took the band aside after soundcheck to warn them it could be rough. I told them if they were in deep concentration and the hoots and whistles and shouts started, try not to let it affect you and continue to give it your best. The end result that night was the audience was as good as gold. In Italy, for instance, they seem to instinctively know the proper time to make noise. It seems to be ingrained in some people and it’s just not very nice. I fear a football sports mentality comes to the fore in American open-air venues. They get over-excited or impatient. They’re waiting for the pay-off. The big riff. They probably only know two Jethro Tull songs anyway. They just don’t seem to have the time when I’m playing an introduction part to let it come naturally in due course. It’s unpleasant and I know it’s going to happen. Hopefully, it won’t happen in New Jersey. I’ll be there so if it does happen, look at me and tell me, “Hey Mike, tell your friends to shut the f**k up!” I’d remember that the rest of my life.You probably would but that’s more the style of Bruce Dickinson, not me. I try to avoid the four-letter words on stage. You avoided dying in 2016, a year so many of my other heroes passed away.And many of them were my friends, or musicians I’ve worked with. There are a lot of deaths because of that romanticized rock ’n’ roll lifestyle. People inherit the mistakes of their youth in terms of drugs and drink. It can catch up to you fast. Like my old friend (bassist) John Wetton (King Crimson, Roxy Music, Uriah Heep and Wishbone Ash). Tony Iommi told me. He rang me up and said Carl Palmer told him. So we chatted about all the dead folk for awhile before getting on to the subject of our own health and mortality because that’s what these things tend to conjure up in your own mind. We may be already be on borrowed time. Tony had lymphoma cancer, which is currently in remission, and a recent scare turned out not to be malignant. So he’s ok. For the moment. He’s looking forward to working with people outside of Black Sabbath. One of them might be me. I was thinking of asking him to join our merry crew for some British shows in December. He was in Jethro Tull for about five minutes, right? It was more like a week. I was immediately struck by the way he played the very first time I saw him in a band that eventually became Black Sabbath. He was different from our generation of blues-based lead guitarists. His style was a direct result of his physical impairment of losing the tips of his fingers early on. He appeared as the lead guitarist of Jethro Tull on “The Rolling Stones Rock and Roll Circus,” a British TV show. But, yes, we consider ourselves most assuredly blessed to still be in business. The phone does keep ringing and people keep asking us to come out to do our stuff, which we happily continue to do. If you’re an astronaut, you’re hanging up the space suit at a certain time of your life. You have to retire! It’s obligatory. Luckily, in my job, 65 came and went and I’m still doing what I do. At least for a little while longer. Jethro Tull will perform November 1 in Red Bank NJ at The Count Basie Theater and November 3 at The Beacon Theatre in New York City.

|

|

|

|

Post by zobstick on Oct 26, 2017 11:10:42 GMT

A proper Ian Anderson/Tony Iommi collaboration..

It obviously won't make up for the loss of Martin to the ranks, but I will be first in the queue to see that!

|

|

|

|

Post by steelmonkey on Oct 28, 2017 17:31:33 GMT

We can still expect surprises !

|

|

|

|

Post by steelmonkey on Oct 28, 2017 17:31:48 GMT

Wait...can you expect surprises ?

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Oct 31, 2017 9:41:58 GMT

www.app.com/story/entertainment/music/2017/10/30/ian-anderson-keeping-music/795202001/Ian Anderson keeping the music of Jethro Tull aliveED CONDRAN, CORRESPONDENT Published 7:00 a.m. ET Oct. 30, 2017 Jethro Tull isn’t touring or recording but the act’s music is still alive thanks to Ian Anderson. Tull’s venerable singer-songwriter will present a collection of songs from his band’s repertoire when he performs Wednesday, Nov. 1 at the Asbury Park Press Stage at the Count Basie Theater in Red Bank. “The guys who were part of Jethro Tull from the early to mid '70s are gone,” Anderson said. “There is only one other person still playing music from that period besides myself. The others no longer play or sadly have passed on. "But I’m still playing those songs. It’s not the other guys, the 32 or so other members of Jethro Tull. Some people get caught up in the name whether it’s Jethro Tull or Ian Anderson but I couldn’t be bothered with that. When I perform it’s not about the band Jethro Tull but the music of Jethro Tull.” The sound of Jethro Tull is unique. Anderson, 70, and his former bandmates crafted an unusual amalgam of blues, folk and hard rock. Jethro Tull was uncompromising and difficult to pigeonhole. “We did what we wanted to do and somehow we were successful,” Anderson said. “We didn’t follow any template. We never had any desire to follow a trend. We just did what we were compelled to do.” Jethro Tull has 11 gold albums and five platinum albums to its credit. Anderson never considered chasing a trend. “That’s how we made it in America,” Anderson said. “We did it by not trying. The same can be said for Led Zeppelin. The more desperate you are, the less chance you have of making it in America. So many British artists wanted desperately to make it in America and didn’t. Look at Cliff Richard. But that wasn’t Jethro Tull. We were about doing something different.” That’s evident by just glancing at Anderson’s instrument of choice, the flute. Flautists and rock don’t mix on paper. “It’s true,” Anderson said. “I knew I’d never be a great guitar player. Eric Clapton was the leader of that pack when I was starting out and I knew that it wasn’t the way I would go. It seemed prudent to find something else. The flute worked for me but I would not recommend it to someone starting out. Go with an archetypal instrument like the guitar, bass, drums or keyboard. I’m the only one to make a go playing the flute all these years. Don’t follow in my footsteps.” Anderson reconfigured Tull classics for “Jethro Tull: The String Quartets,” which was released in July. The album features Tull favorites as classical music compositions. “The point was to realize some of the classic Tull songs into something that was classically inspired. It was a challenge presenting each song in a different way. But it wasn’t a stretch to present the songs as classical music compositions.” The long, lanky Anderson will mark his 50th year as a recording artist in 2018. “I just keep moving along,” Anderson said. “I’m fortunate that people still care about the music. They still come out and support the live experience. I still love doing this. If I didn’t, I can assure you that I would not be doing this but it remains an enjoyable experience.” IAN ANDERSON WHEN: 7 p.m. Wednesday, Nov. 1 WHERE: The Asbury Park Press Stage at Count Basie Theatre, 99 Monmouth St., Red Bank TICKETS: $39 to $59 INFO: 732-842-9000 or www.countbasietheatre.org

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Nov 3, 2017 9:02:17 GMT

folioweekly.com/stories/life-is-a-long-song,18575 Life is a Long SONGRock legend Ian Anderson hits the half-century mark of following his own mercurial musePosted Thursday, November 2, 2017 2:01 pm story by DANIEL A. BROWN Ian Anderson remains an inscrutable presence in the music scene. The Scottish singer-songwriter and multi-instrumentalist who founded Jethro Tull in 1968 has led that band from its blues-rock roots into commercial FM classic rock hero status, while swimming into side streams both unconventional and admirably uncommercial. Over the years, jazz, classical, even traditional British music have all been utilized by Anderson as fodder for songs. If there is a recurring quality to Anderson, and by extension Tull’s music, it has been one of a kind of decisive commitment to continually pursue something else. Flipping through Jethro Tull’s sizable discography, there is a kind of logic in the themes—loss, environmentalism, and gritty existentialism are but three. For many, Jethro Tull helps us celebrate both passion and apostasy. The band is commonly considered to be forefathers of the ’70s progressive rock scene. Yet their de facto masterpiece of that era, 1972’s Thick as a Brick, was a Monty Python-inspired spoof of the very scene that soon held Jethro Tull aloft. Anderson is a signifier of classic rock, both in sound and image. His Albion-blues-belter voice and Rahsaan Roland Kirk-style flute riffing makes Jethro Tull’s music instantly recognizable, as does the image of Anderson in performance, standing on one leg, with bushy hair and maniacal eyes, a wisecracking, droll Highlander challenging the audience from the spotlight. Anderson and various permutations of the band have stayed busy since the band’s heyday. In 1989, Jethro Tull won the inaugural Grammy Award for Best Hard Rock/Metal Performance Vocal or Instrumental for their album, Crest of a Knave. Although nominated, Anderson figured the band had no chance of winning and didn’t even attend the event. The win was a much-ballyhooed upset, especially since Metallica were the hands-down favorites to snag the award. In response to the furor, Anderson commented in his own typical and droll style: "Well, we do sometimes play our mandolins very loudly." Most recently, Anderson and Tull keyboardist John O’Hara collaborated with the Carducci String Quartet for Jethro Tull: The String Quartets. Anderson’s success working in classical settings goes back to Jethro Tull’s earliest roots and his latest is no exception, featuring inventive interpretations of band songs including “Locomotive Breath,” “Living in the Past,” and "Sossity, You're A Woman." Devotees of Anderson and his band run the gamut from metal to moody songsmiths. Iron Maiden famously covered “Cross Eyed Mary” while neo-prog bands Dream Theater and Porcupine Tree have attempted to evolve Tull’s sound, if not musical philosophy. Even Nick Cave has vocally espoused his love of Tull, going as far to name his oldest son Jethro after the band. Ian Anderson is hitting the road this fall with his current lineup, which includes O’Hara (keyboards), David Goodier (bass), Florian Opahle (guitar), and Scott Hammond (drums). This week they return to Northeast Florida with a show at Daily’s Place. Folio Weekly interviewed Ian Anderson via telephone, as this author sat in a minivan in the parking lot of a Cracker Barrel 50 miles south of Nashville, Tennessee–a quintessential and bucolic progressive rock setting. Folio Weekly: What was the impetus behind the Jethro Tull: The String Quartets album? Ian Anderson: Well, it was one of those projects, which I wanted to take off the list while I could. Last year while we were on tour, I had the opportunity to work with our keyboard player, John O'Hara, who is a classically trained orchestrator and percussionist. And he and I worked backstage and in dressing rooms and hotel lobbies, wherever we could really, to work on ideas for the string quartet album, for which he arranged the quartet parts. It was really just to realize some of the more classic Jethro Tull songs in a more pure, classical-sounding setting. I’m not trying to turn it into classical music, because it’s not…apart from one piece, that is. But most of it was really about trying to show myself and show the fans that a good tune, or even a halfway decent one, can undergo an interpretation, which dresses it up in a new suit of clothes. It’s still the same old body underneath and it’s still the same old elements and melody and harmony and rhythm; which essentially is what music is. But, um, giving it a different context in which to operate and I find that interesting, and a little challenging. But I think it worked pretty well. Although I’ve always been at pains to tell if our fans like their meat and potatoes, or in your country, if they like their meatloaf and gravy and mashed potatoes, the way mom used to make it, is probably a different album for them. It seems like a logical extension of the Tull catalog, since it seems like you’ve always been comfortable working with those classical textures in the music. Well, I first worked with a string quartet in November of 1968 when I recorded a track called, “A Christmas Song.” So it was very early on in the Jethro Tull story that I took to working with string sections and chamber orchestras and they appeared on many Jethro Tull songs throughout the ‘70s. And of course in the last 10 or 15 years I’ve done quite a few orchestral concerts around the world. So I’m not a stranger to working in that context. But I think when you strip away the drums, and the bass, and the electric guitar, and deal with a very pure and simple format—which is, two violins, viola, cello, a little flute or vocals, in our case, a little piano—you’re left with a very simple and clean setting. It’s the musical equivalent of an Apple MacBook. It has that elegance that is attractive. So this isn’t the first time I’ll do this and hopefully it won’t be the last. I don’t have any intention to take it one the road as a string quartet tour because I think that’d be stretching credibility a bit, to perform. Audiences will always imagine that, halfway through, there’s going to be a drum solo. (Laughs) Some of the musicians in the current Jethro Tull lineup are fairly young players; before signing on, how familiar were they with the earlier music? There were certainly a couple of members of the band who weren’t around or born when the Jethro Tull story was happening. But you know these are musicians who’ve grown up playing different kinds of music and they have absorbed the Jethro Tull repertoire; not obviously all 300 songs. But this band now can easily play 100 to 150 of the Tull songs onstage. But these are guys who’ve immersed themselves not just in the music of it, but also tried to get inside the heads of the musicians who, in some cases, played that music decades ago. I think it’s true to say, whilst the guys in the band today can play all of the repertoire from ’68 through to the present day, you couldn’t say the reverse: some of the guys who were in the band back then wouldn’t really have perhaps the technical skills or musical styles available to them to play all of that repertoire. They were very important members of the band during the time they were in the group, but things move on. And of course, in many cases, those musicians are no longer playing music. They are old guys who’ve given up, or in some cases, sadly they are no longer with us. It’s not feasible, for instance, next year will be the 50th anniversary of Jethro Tull… That’s right! Congratulations. That’s really quite a milestone. Thank you. And we won’t be wheeling out coffins on the stage or have onstage paramedics for that tour. You could have the Mayo Clinic sponsor the tour. Yes, I suppose you could just try and stick to touring in major cities with venues that are close to hospitals. But joking aside, and it’s not really that funny I suppose to joke about those who are feeble these days or no longer with us, but the reality is, it’s been a long time. I’m 70 years old and have been lucky enough to enjoy good health and am still able to do what I do. But it’s not everybody who can manage that. As I’m sure you’re aware, in these last few months there have been quite a few stalwarts of the ‘60s and ’70s who’ve passed away and I’m sure you can expect to see an increase during the next years. All of those founding members of the great days of classic rock music, if they’re not already gone, they will be dropping like flies in the next few years. And sooner or later, me too. Well, you probably have 50 more years in you…the Centennial Tour. Well, people come up with these encouraging remarks (laughs), but I just kind of groan and say, “Who are you kidding?” You mentioned how your current band knows your repertoire, and I guess there is an assumption that you have to play certain well-loved tunes for the fans. But, that being said, what are the songs that you personally prefer to focus on in concert? Well, my tastes in the music of Jethro Tull over the years are not that different from the audience. The ones they seem to focus on, some of the mainstream heavy hitters of the Jethro Tull repertoire; well, I tend to agree with them. In all honesty, there are only one or two songs I think that are popular, particularly in America, which I don’t like to do. Two songs that I don’t like to do are “Teacher” and “Bungle in the Jungle.” And it’s only because they were deliberately written in a commercial, more pop kind of style that I feel a little self conscious about. But that’s probably it. In fact, those songs aren’t particularly popular in other countries of the world. It’s just that in America, I suppose, they were considered to be a couple of important tracks. Happily, there are other ones that are more important to American audiences and to me, too. So if there’s something I really don’t want to do, I won’t do it. If it’s in the setlist, it must be something I have a deep love for, as you do for your children, your grandchildren, your cats, your dogs…you know, there’s some very profound emotional attachment. And I wouldn’t play anything onstage that I was even remotely uncomfortable with or ashamed of. There are times when I’m up there when I think, “Wouldn’t it be nice to have a go at ‘Stairway to Heaven’?” Then I realize, “No, I’m not the guy who sang that” and probably wouldn’t do it justice. But there are things that you sometimes get a little idea about doing some songs that I hadn’t written, but I think it would be a little bit cheesy to do that. Jethro Tull, as you might have heard, is usually categorized as progressive rock, but the band has always seemed to travel against the grain. In the ’70s, you were never as “rigidly” prog as someone like Gong or Gentle Giant. You had all of these different musical approaches that went from classical and jazz that would then shift to traditional music and then the heavy songs that helped create metal. Did that progressive rock label ever seem inaccurate to you in some way? I don’t believe you can compare us, in a general degree, with the “arch” kind of “noodling” prog rock bands like Gentle Giant or perhaps Yes, or even early Genesis. Jethro Tull is really more about me as a songwriter trying to come up with songs that were interesting and developmental, that sometimes fit with the label “progressive rock.” But it became termed as “prog,” as the British press did in the early ’70s, which was usually used with a sense of sneering and disparaging, begrudging interest in the music. Because prog rock could be a little too grandiose and self indulgent, and I think that was interesting as a piece of music history, but I’m not sure it passes muster today. But there are bands today that indeed follow that particular approach. My good friend Steven Wilson [of UK band Porcupine Tree], who has remixed many of the classic Jethro Tull classic albums, he in his previous band identity and now as a solo artist with a band, he’s very much someone who’s part of the contemporary progressive rock tradition. And I suppose bands like Dream Theater. So it’s never really gone away. I think that probably bands today like Steven Wilson or Dream Theater have a little bit more of an ability to not fall into that trap of self indulgence. Which I think was the case with a lot of bands back then. I mean, I have to put my hand up and say, “Yes, for a couple of albums we fooled around with a slightly over-the-top approach as well.” But I like to think the songs were more identifiable as songs and weren’t really burdened with much instrumentally showing off. We weren’t that good of musicians, when you had Genesis with Steve Hackett as the guitar player. They were great, great musicians of instrumental prowess. You’ve been a longtime, vocal advocate for things like nature conservancy and environmental action, animal rights, and climate change. Do you think that, as a species, we have the potential to change—or are we entering an irreversible doomsday scenario? Well, it’s not looking good, I have to say. And the current U.S. administration’s policy with Trump spells a huge disappointment for people all over the world, in hoping that America would take the lead in really addressing the issues of climate change. But you know there are other issues attached to that, too, including global population and no one wants to go near that. Because you can’t tell people how many babies they’re going to have. But what you can do is alert people to the issues, which, according to the United Nations’ latest figures, would demonstrate something in the order of 11 to 13 billion people on planet Earth by the end of this century. Indeed, the seven billion that we currently have is set to be something like 10 billion by 2050. Most of that increase is in Africa and Asia, where family sizes are enormous. It’s all about education of women, it’s all about giving women rights and equality throughout the world. Because generally speaking, when women have an education they choose to have fewer children. They have other things that they want to do in life rather than be subject to the patriarchal society where men seem determined to exert their prowess over all. Rather than having a Harley Davidson between their legs, men have as many babies as possible. It’s like a status symbol; it’s like a collection. In the way that some people might collect baseballs or signed photographs of baseball stars, some men just choose to have a lot of babies. Mind you, one child is a blessing. Two children are a God-given gift. Once you go beyond that, it’s the start of a collection (laughs). Personally, I’m not really into collecting children, or grandchildren, for the matter. I told my son-in-law [Andrew Lincoln, of The Walking Dead] that there are two bricks with his name on them that would smash his testicles into a mush should he attempt to impregnate my daughter again.

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Dec 16, 2017 8:45:35 GMT

60stoday.com/2017/12/15/a-conversation-with-ian-anderson-of-jethro-tull/A Conversation with Ian Anderson of Jethro TullBY AMY BALOG DECEMBER 15, 2017 This month marks the 50th anniversary of Jethro Tull’s formation, even if the band didn’t acquire their final name until early 1968. Although Ian Anderson has already finished writing the group’s 22nd LP, he has decided not to release it until 2019, so he can focus on celebrating Jethro Tull’s history with a special anniversary tour next year. We asked him to reflect on the past five decades, and to share some details about the content of the 2018 shows and the sound of the new record, among many other things. When Jethro Tull first got together at the end of 1967, would you have thought that you’d still be doing the same thing 50 years later? The band did indeed get together in December 1967, but it wasn’t until 2nd February 1968, I believe, that we became Jethro Tull, and that was the key point. We were playing at the Marquee Club in London, for our fourth attempt, I think, to curry favour with the management of the club. At that point, there was no reason to believe that any success that we might have would be anything more than short-lived, because that’s the story of pop and rock music – you know, they come and they go. There were lots of one-hit wonders. We were just grateful to have something to get out of bed for and hopefully make enough money just to survive, which we did for a few months until we began to build up a following. Then we released our first album, which did quite well, and it put us on the map. Maybe after a year or two, I began to think, “if I don’t do anything too stupid, maybe I could have a career in music” – not necessarily as a performing musician; maybe as a record producer or a manager or working for a record company, or just something connected with the music world. And after four or five years, I began to think, “maybe I can go on performing”. Also, many of my musical heroes from when I was a teenager, people from the world of jazz and blues, were still playing music. They were playing until they died. Some of them, of course, weren’t very old when they died, because a lot of them were addicted to drugs and alcohol, and quite often didn’t make it to a glorious old age. But the prospects definitely seemed a little brighter after four or five years. And at this point in my life, I have to think that I will probably die with my boots on, like any good cowboy hero in a 1950s western. It’s the good fortune of people in the world of arts and entertainment that they’re able to continue as long as they feel fit and able, not having to retire at the age of 65 and learn to play golf – god help us! How do you feel about ‘This Was’ all these years later? Is it special to you? What’s special to me about it is the infinite wisdom of a 23-year-old! The choice of the name, I think, was a really important decision that I took. I suppose, by the time we got to preparing the artwork for the album, I’d already started to toy with some new songs, which, I hoped, would be the material that we’d play and record for our second album. And it was very different to the imitative blues format that we began with – that was a slightly cynical thing to do, because blues was essentially the underground music form of the clubs and the pubs, and it was a way into music, but it wasn’t something that I very much enjoyed listening to as a music fan. It wasn’t what I thought I was equipped or indeed entitled to do, because I’m not black and I’m not American. So I felt I should move on and do something that was a little more close to home, in the sense of my own culture and background, and so working on those songs, it seemed like it would be a departure from our first record and our first performances. That’s why I decided to call it ‘This Was Jethro Tull’, which was a very fitting way of pointing out that already this was something in the past. And that also led me to the idea of the band all dressing up as old men on the back of the album cover. The front of the album cover had no title on it, which the record company was extremely upset about. They said, “you’ve got to have the name of the band and the album title on the front cover”, and I said: “Why?” And they couldn’t really give me a good reason, so I compromised, and we put it on the back cover. I thought that the fact that there is nothing on the front cover would get people talking, and, of course, it did. And the band being made up to look like a bunch of wizened old men was part of the package, so I think it worked our fairly well, in the sense of marketing and promotion – such as it was in those days. You’re doing a handful of Christmas shows this month. Since you wrote quite a lot of anti-organized-religion songs in the past, I was wondering why you chose cathedrals as venues? Those songs are not anti-religion, but “anti-the-way-it-is-taught-and-conveyed”. People in my generation grew up with the legacy of an old-fashioned school system, where we were taught religion in a very closed-door context. It was not appropriate to question the religious instruction master, who was the headmaster of our grammar school, and to question the word of god, as it was written in the Bible. I felt that religion wasn’t being passed on to us in a way that was constructive and relevant to our lives in the future as young men growing up in a world that was ever-changing, and changing faster than anybody’d ever seen it before – there was a real cultural revolution happening. So you’re not against the idea of religion and god? I’ve never been against the idea of religion or god. It is a state of humankind that we yearn for some kind of a spiritual connection and we want to have answers, even though many of us in our hearts know that our questions are unanswerable; that’s not the point. But it’s part of who and what we are as creatures: we feel there must be more than a finite existence. And religion serves a purpose, whether it’s Christianity, Judaism or Islam. And wherever the monotheistic religions are practiced, I believe that we are, in our different ways, addressing the same god, the same idea of god. This doesn’t sit too well with the head-hunters of the different religions, because they all think that everybody else’s god is a false god and it can’t be the same – but, goodness me, of course it is! Even the Hindu religion, with its pantheon of gods to suit every mood and every day of the year, still comes down to being the manifestation of a single deity, a single creator. And you choose the one or the ones you want to follow. Religion is also responsible for a huge number of dreadful things in the world, that people do in the name of religion. Right now, of course, Islam is the bogeyman, because it’s all too easy to confuse the idea of Islam as a faith with Islamic extremism. But, of course, Islam is a very pure and beautiful expression of a religious conviction – it just happens to be a very convenient excuse for those who want to go out and create madness and mayhem. Frankly, those people that we talk about as being terrorists and extremists are essentially spoiling for a fight, in the same way as they would on the terraces of the football ground in the 60s or the 70s. They just want a punch-up, and religion gives them an excuse, but that doesn’t make me want to condemn any individual religions or religion collectively. I don’t call myself a Christian, but I’m a huge supporter of the Christian church, because it’s my cultural background. I believe in supporting Christianity, particularly the great and beautiful buildings that have been designed and maintained over the years. They are a hugely important part of our world, particularly in the UK, where we have so many beautiful cathedrals, sometimes in quite small cities. They’re community assets, and many of them are struggling to survive, particularly Bradford and Peterborough, which I’m playing this year. I do my little bit to support those buildings and help pay for the heating bills and the staff’s wages for another couple of days, which is about all my concerts are able to generate. We do what we can. And I invite the audience to join in and think again about the value of these community assets, whether they’re Christians, or whatever their persuasion or lack of. You also have the Jethro Tull 50th anniversary tour coming up next year. What is the set list going to look like? The tour next year will be 10 months of gritting my teeth and going with the flow, and trying desperately hard not to be a party popper, because celebrating things gone by is just not me. I don’t do birthdays and anniversaries – I just feel really awkward about it. But, you know, on the other hand, a little noise inside me a few months ago began to say: “Listen, it’s only going to happen once, so go with the flow and try and enjoy it. Use it as an opportunity to perhaps consider the origins of the band, and to celebrate not only the music of Jethro Tull, but also the 33 musicians that have been part of the band over the years.” It’s been an ever-changing line-up, and they have all given months or years of devoted attention to performing the music, even when they weren’t in the band when that music was performed for the first time. So it’s about celebrating something, and I can just focus on 10 months of touring, when we will do the expected thing. And the expected thing is to wallow in undiluted nostalgia for two hours on stage! There is a set list, but it may change. It will very likely focus mostly on the first 10 years of Jethro Tull, when the band became internationally successful. By the time we’d been going for 10 years, we’d had the impact on all of the countries that we’ll be playing. All of those countries had found Jethro Tull somewhere along the way, not necessarily at the beginning, but perhaps in the late 70s – countries as diverse as Russia, India, and, to some extent, Japan, and places around the world that perhaps we never thought we might reach, but, of course, we did, and we played at all those places. And some of them we will be playing again in 2018. Is there a chance that we can hear some new material at the shows? There is new material, but you won’t be hearing it until 2019. These nostalgic shows would be the wrong place and wrong time to introduce the new album; that would be a diversion from what it is we’re really doing, so I’ve decided to postpone it. We’re halfway through recording it at the moment. In January or February 2018, I’ll probably make a big dent in the remaining work that has to be done, but we’re talking 2019 for a new studio album. In a way, it’s pretty frustrating, because I already completed writing it in January or February this year, and we did the recordings mainly in March. It’s like having to forget you’ve done something, because to keep engaging with it would make it seem really old hat by the time we released it. So I’m just having to push it to a far part of my brain until I’m ready to do something more creative with it, and then, hopefully we will get it into the marketplace in 2019, probably around March. Musically, is the new album going to be more similar to your recent solo work, or are you trying to recreate the classic Jethro Tull sound? There are many ways of considering Jethro Tull through the years, having begun essentially as an imitative blues band and gone through eclectic musical eras that sometimes went off into more folky or progressive rock or sometimes hard rock directions. So it’s very difficult to say what is the classic Jethro Tull sound, as there’s probably four or five of them, to say the very least. My approach when writing music is trying not to get too bogged down with trying to write in a particular way. It’s much better to have a sense of freedom and make the music that feels right to you at the time. If you have to put a label on it later on, then it’s probably best to let somebody else do it. I don’t consciously think too much about it, other than trying to create a balance of dynamics, tempos, keys and time signatures to make it interesting musically. That’s what I’ve done since the very beginning and that’s what I do today. The album is a mixture of heavy rock music, some rather spacey kind of acoustic music and electronica, so it’s not like having 12 tracks that all sound very similar to each other. I find it very boring when it’s the same instrumentation, the same musical idea being trotted out for 60 minutes of meat and potatoes. You’re asked about music all the time, but you’ve also written some of the most distinctive lyrics in rock. Are there any writers, poets or other songwriters that have influenced you? Well, the answer to that is pretty much no. Once I became a professional musician, I began to listen to less and less music. Particularly in terms of lyrics, I just don’t want to be influenced by other people in the same profession. By the early 70s, I was consciously trying to avoid music in my life. My average day consists of probably a couple of hours of music, because I’m always going to be playing music just for fun or rehearsing something or working on some new ideas. I think two or three hours of music a day is probably enough, otherwise it becomes an overkill. You really just have to have fresh ears, and silence is so important in my world. It can be silence in my office or just the space between the musical notes, which I try and remind myself I must remember to preserve, rather than a cacophony of machine gun scattering of music, which the overly enthusiastic, vigorous songwriter can sometimes be guilty of – and I’m certainly no exception. I think I’m mostly an observational writer, and I think it comes from having studied painting and drawing when I was younger. I’m used to the idea of line and form, and tone and colour in the pictorial arts, and as a writer of music it’s very easy to take those same words, which are also describing elements of music, and use them in a painterly way as a musician. I tend to write songs about people in a landscape. I’m not a portrait painter; I don’t like close-ups of the face, and I’m not a landscape painter, because however beautiful the mountains and the rivers might be, if there aren’t any people in them, it all seems a little empty. I like to have context for the characters that may be written about, and sometimes I sing in the first person, but it’s not necessarily autobiographical, nor is it me displaying the personal angst or emotion that I’m asking to people to share or identify with. I’m playing a character; I’m like an actor on a stage and I’m performing the role through music, whether it’s recorded or live. So just because I say something in the first person, doesn’t mean it expresses my personal character attributes, failings or philosophies. Although most pop and rock lyrics are about the bleating of rather sad souls who haven’t got much to write about anyway, so it’s not too difficult to avoid repeating what they do. Sometimes you just have to stop and look around you, and you can find inspiration for music and song lyrics in places where you didn’t think you would. It’s just a matter of stopping and being an observer in a world where you have to try and think outside the box sometimes. Einstein came up with some radical ideas as the observer of the universe, because he was able to think outside the box and stop and consider something that other people had just overlooked. I think that’s the job of an artist, too; to sit and find other ways to look at something that others just glance at and walk on. Sometimes you have to stop and take a closer look at something to find something else in it. I am probably influenced as a lyric writer by people, but not from the world of pop and rock music. I’m more likely to take inspiration from factual material, because I do tend to read quite a lot of stuff that is a bit more philosophical, about the state of man and the world we live in. I also read some fiction; my hat goes most readily to John le Carré, who over the years has turned out an enormous amount of material and is a thinking man’s thriller writer. He does tend to come at things with an idea. He has a bee in his bonnet and he goes out there to work it out through characters, which he devises almost like a script writer writing a movie. Dialogue is a great strong point of le Carré’s work, and so is the pace. His books tend to start slowly; you’ve got to struggle with the first 30-50 pages, and then it begins to pick up a little bit. It almost always satisfies, in the sense of having that dramatic, dynamic kind of a range, which, I think, is very important when you’re writing fiction or music. There has to be a climax when you’re writing fiction, which is similar to a musical climax. So his work is an example that I try and follow, in terms of the vocabulary, characterisations and the development of ideas. But, of course, it’s a very different world to writing lyrics – I doubt that I can write fiction, and I doubt that le Carré is a rock music lyric writer in his spare time. He probably has little interest in that world; they’re like parallel universes, but they do touch edges sometimes.

|

|

|

|

Post by maddogfagin on Jan 26, 2018 15:35:04 GMT

www.psychologytoday.com/blog/brick-brick/201606/ian-anderson-s-progressive-pathIan Anderson’s Progressive PathFounding member of Jethro Tull is always moving forward Michael Friedman Ph.D. Posted Jun 20, 2016“So when you look into the sun,

And see the words you could have sung,

It's not too late, only begun.